NEWS

Reflection: What We Talk About When We Talk About Holiness

Recently, I was visiting a parishioner in the hospital and he made a great point: sometimes, those of us who have been raised in the Church use certain words and we take them for granted without pausing to consider what they truly mean. Words like Glory, fellowship, and salvation are so pervasively used that we often lose sight of their meaning. I was reminded of this phenomenon this week at St. John’s College where we recently launched a book discussion group with some of our St. Paul’s students. We were discussing C.S. Lewis’ masterful book The Great Divorce and, in the course of the conversation, I threw out the term “grace.” Someone asked me to define that term and I balked, realizing that it denotes a much more complex idea than I was prepared to explain in the moment.

A common term we use a lot, and the one I want to focus on today, is holiness. We talk about God as holy and our desire to acquire holiness. But what does it mean to be holy?

Kadesh. Hagios. These are the Hebrew and Greek words most commonly used in the Bible for “holy.” In Latin, the term is sanctus from which we get our word sanctuary, a holy place set apart for the worship of God. Holiness refers to set apartness. When it comes to morality, this carries a sense of purity but it refers to more than that. Usually, when people are set apart, they are set apart for something.

After passing through the Red Sea, Moses and Israel sing, “Who is like unto thee, O Lord, among the gods? Who is like thee, glorious in holiness, fearful in praises, doing wonders?” In I Samuel 2:2, Hannah, the mother of Samuel, echoes her forefathers’ sentiments by praying, “There is none holy as the Lord: For there is none beside thee: Neither is there any rock like our God.” It’s God’s holiness that causes him to be worshipped in heaven in Isaiah 6:3: “Holy, holy, holy is the Lord of hosts: The whole earth is full of his glory.” God is holy because no one else is like him. As our Creator, God is completely and utterly distinct from his creation. While us creatures can be good or bad, God is perfect; while we waiver between virtue and vice, he is constant. It’s not that God acts a certain way and proves that he’s holy; the opposite is true: God is holy and so his actions are holy.

In the Old Testament, one of the implications of God’s holiness is that the people of Israel, his Chosen People, were called to be holy. Because God is holy and Israel was to represent God to the world, they were called to be holy too. In Leviticus 19:2, God instructs Israel, “Ye shall be holy: for I the Lord your God am holy.” Israel’s holiness was always derivative of God’s holiness; they could become holy by participating in God’s life. How were they to do this? The answer is the Law of Moses which teaches us how to live in ways that are pleasing to God. Israel’s Law set them apart from their neighbors. They had to eat differently, live differently, and worship differently than the nations around them.

The New Testament calls the Church to an analogous holiness. In fact, the kind of holiness Christians are called to is more radical because it’s from the inside out. One of the problems with law in general is that it is behavior management. One can abide by the letter of the law and still miss the real purpose. The Christian law is interior. It’s not enough to not commit adultery because you shouldn’t even lust. It’s not enough to not murder because you shouldn’t even get angry at someone in your thought. This is a totalizing holiness that cuts to the heart of the person. That’s why St. Paul summarizes Christian ethics with a singular word: love. “He that loveth another hath fulfilled the law” (Rom 13:8). In a world characterized by violence and hatred, the love God shows us, and that we can then extend to others, sets us apart.

But what is holiness for? The answer has two parts that connect like a graph with vertical and horizontal axes. The first and primary reason for our holiness is the vertical dimension. It’s through holiness we worship God. “Present your bodies a living sacrifice, holy, acceptable unto God, which is your reasonable service” (Rom 12:1). In the Old Testament, an animal might be sacrificed to God as a picture of the coming redemption through Jesus Christ. Now that redemption is here, we respond not by killing an animal but by living into the fact that we have been set apart by God. We understand that we were bought at a great price (I Cor 6:20) and so we offer God ourselves in an attempt at reciprocity. As we pray during the Holy Communion liturgy, “although we are unworthy, through our manifold sins, to offer unto thee any sacrifice; yet we beseech thee to accept this our bounden duty and service” (BCP 81). For Christians, being holy means offering God every part of who we are, not holding anything back, but giving him our whole selves.

The horizontal axis of holiness is also indispensable. “Thou shalt love the Lord thy God with all thy heart, and with all thy soul, and with all thy mind. This is the first and great commandment. And the second is like unto it; Thou shalt love thy neighbour as thyself.” Humans are created in God’s image; if we don’t love others, we can’t love God and vice-versa. Holiness is not an opportunity to look down on others, like in the instance of the Pharisee who uses his perceived holiness to look down on the poor publican. Rather, our holiness should cause us to reach out towards others, to love them better, as a way of evangelism. This was the case for Israel in the Old Testament. Psalm 67 draws out the universal intention of God. He chose Israel so “That thy way may be known upon earth, Thy saving health among all nations. Let the people praise thee, O God; Let all the people praise thee” (vv. 2–3). One of my favorite novels is The Samurai by Shusaku Endo. Without giving too much away, one of the characters performs an act that he knows will bring him martyrdom in Japan. When a puzzled government official interrogates this character as to why he would do something that he knows would bring him death, he responds by saying “Your question itself is the answer. You have said that what I did was ridiculous. I understand that. But why did I knowingly perform such a ridiculous act? Why did I deliberately do something that seems so lunatic? Why did I come to Japan knowing I would die? Think about that that sometime. If I can die and leave you and Japan to deal with that question, my life in this world will have had meaning.” This character makes a peculiar decision for the purpose of Japan’s salvation. The question of Israel’s holiness, and now, the Church’s holiness should be a “splinter in the mind” that causes people to wonder why we act the way we do. That wonder should give way to awe as they grasp the transformative mystery of God’s love and power.

If it’s true that holiness has a two-pronged goal of worship God and bringing the nations to him, the remaining question is how do we become holy. In one sense, at Baptism, you are made holy because Baptism seals us with the Holy Spirit and marks us as Christ’s own forever. Still, holiness is an area in which we can grow as we participate in God’s life. This begins with the grace he gives us at Holy Communion: just like he fed the people of Israel with manna from heaven as they wandered toward the Promise Land so he feeds us with himself as we approach our heavenly destiny. But this is the beginning, not the end. The story that’s played out every Mass should be transposed into our own lives. This happens when we recognize not only who we are but whose we are.

Old Time Bible Hour: Tuesday, August 29, 2023 - St. Gregory of Nyssa on the Life of Moses

The Old Time Bible Hour is a once-a-month session where we look at how Christian who have gone before us read the Scriptures.

Here at St. Paul’s, our Old Testament readings on Sunday are about to take us through the life of Moses. Prepare by attending the Old Time Bible Hour as we read and discuss St. Gregory of Nyssa’s brilliant treatment of the Moses story from The Life of Moses.

Gregory of Nyssa, a prominent figure in the fourth-century Christian church, was born in Cappadocia, Asia Minor, around 335 AD. Renowned for his deep theological insights and philosophical prowess, he played a pivotal role in shaping the doctrine of the Trinity and Christian mysticism. As a theologian and bishop, Gregory authored numerous influential works, delving into topics ranging from the nature of God to the soul's journey toward union with the divine. Without him, we may not have the Nicene Creed. His legacy endures as a beacon of intellectual rigor, spiritual exploration, and devotion to Christ's teachings.

Our discussion will take place on Tuesday, August 29. Evening Prayer will be prayed at 6:30p in the Chapel followed by the discussion at 7p.

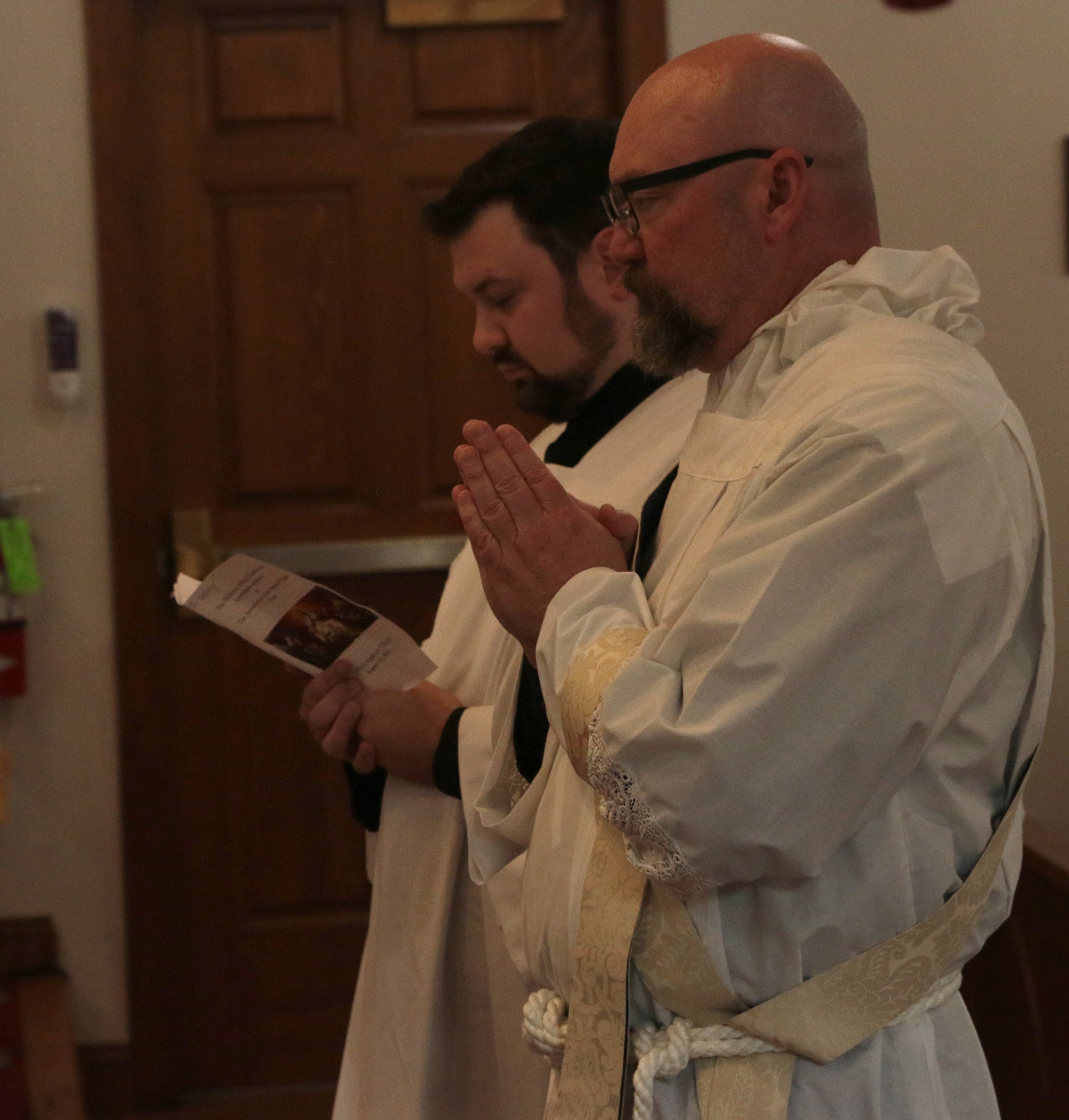

August 13, 2023: A Wonderful Episcopal Visitation

A hearty thank you to everyone who made this Episcopal Visitation weekend a great success! Seven confirmations, seven receptions, and one ordination made for a very busy and exciting weekend!

My Church, and Memories: They Do Come Again

By Eva Gasperich

From the Evening Capital

Tuesday, September 9, 1958

Dcn. David and I were rummaging through the water closet the other day and found a poster board with an old article about St. Paul’s Chapel that ran in the Evening Capital on Tuesday, September 9, 1958 by a woman named Eva Gasperich. We thought it was so neat to have a firsthand account of some of the history at St. Paul’s and wanted to share it with you. Here it is:

In the rugged days of early Anne Arundel, people went to unheated churches and worshipped God on their knees on cold, bare floors. They read the Holy Bible daily, studied their church catechism and prayed out loud in the family circle night and morning.

In Anne Arundel county St. Anne’s in Annapolis was the center of the Protestant Episcopal faith. But the rough dirt roads caused country people great hardship to attend. in order to be on time for Morning Prayer, they had to drive to Annapolis with horse and carriage the day before, and put up over night. to alleviate this situation, sometime in 1730, the Episcopal Diocese had a chapel erected in the North Severn River area on the old Chesterfield Road and called it the Chapel of Ease.

For 77 years hereafter this chapel served the simple needs of the few country Episcopalians, scattered through Severn Parish. Then on a warm Whitsunday a great wind-storm swept in from South River to the Severn and destroyed the Chapel of Ease. A tablet, erected by the Daughters of the Revolution, now marks this old site.

Meanwhile, Francis Asbury, the famous circuit rider who followed the Wesleyan movement from the Episcopal Church, and was the first Methodist Bishop in America, had established special headquarters at Brooksy’s Point on the Severn River, called Asbury’s Station. This also is marked by the D.A.R.

When the Chapel of Ease blew down, one William Thomas Turner, with an inspiration for Christian unity, offered a piece of his property called Warfield’s Plains at Severn Cross Roads for a community church to be jointly built and shared by Methodists and Episcopalians. The sects were financially hard pressed and few in numbers in those days.

This plan was gratefully accepted. The elders met and planned. Every man who could handle a saw and an axe came forward to work. What financial resources the two denominations could muster were pledged.

When the first church opening was held, both denominations took part. The sermon of the day is attributed to Francis Asbury.

It was a stupendous event for many sociable helpful years afterwards Methodists and Episcopalians held alternate services in this building. It was called Old Cross Roads Church. Ivy-covered brick Baldwin Memorial stands there now facing on the General’s Highway.

As times advanced and the population increased, the Episcopalians, let by Basil Hall, who lived nearby, separated from Old Cross Roads Church. Three miles further down on Chesterfield road the Episcopal element built a brick church fired from a clay field opposite the side and named it St. Stephens. This was sometime in 1843.

Severn Parish was then formally separated from St. Anne’s. The Methodists bought out the Episcopal interests in Old Cross Roads. The proceeds were set aside for a chapel fund.

At Crownsville Station of the Annapolis and Elkridge steam railroad, there was a corral in a grove where people taking the train tied their horses. This lot was owned by two spinster gentlewomen named Brown. They were weary of travelling over awful roads in a creaking carriage either to St. Anne’s or St. Stephen’s and offered the old corral to Severn Parish upon which to build a mission chapel. With the funds from the sale of Episcopal interests in Old Cross Roads Church, and pledges from the country faithful, St. Paul’s Chapel was build in the livestock grove at Crownsville in 1850, when Maryland was sorely troubled by the War Between the States.

It was a small frame structure, but Gothic-styled, with steeple and bell and it was hand-hewed, with 16 pitch-pine pews, including four in the slave gallery at the rear. On either side of the steps to the front vestibule, there were smooth chestnut stumps placed where ladies on horseback might alight and mount with ease at the church entrance. Hitching rings were attached to the trees. At the rear of the church was a small carriage shed for the minister’s convenience. Attached to the shed was a vine-covered wooden outhouse divided discreetly in two sections, one for ladies, the other for gentlemen. A little way down under the bank near the Annapolis and Elkridge Railroad tracks, there was a flowing spring where a wooden bucket and a drinking gourd were kept for the thirsty. Here churchgoers filled pewter pitchers with fresh water for baptisms and the minister’s ablutions in the vestry.

Severn Parish in 1860 was pleased with the little new mission, set so conveniently between the railroad tracks and the public road from Baltimore to Annapolis, the very same road traveled alternately by the Continental and British armies during the early makings of America. Along this road the seed of the golden gorse of Scotland, let as waste, had sprouted, rooted and was blooming in profusion. To this very day the colors of Scotland are found in bloom in the Springtime.

St. Paul’s Chapel still stands there, exactly as first built, but the railroad tracks are gone, and the historic road winding by is hard-surfaced now and is known as The General’s Highway. This was the route taken by General of the Continental Army, George Washington, when he went to Annapolis to resign his commission.

It was in a time of tribulation that St. Paul’s Chapel was built at Crownsville. The first services were a prayer for peace between the States. And when the sad years were over, the parishioners gathered there to give thanks for the end of strife and to mourn the dead.

By not seceding Maryland was spared much of the savagery of conflict but sympathies were divided and hearts were torn. The Annapolis and Elkridge trains chugged by daily with soldiers and supplies for the front. Union soldiers patrolled the road and checked the congregation at worship.

At St. Paul’s Chapel the old families have gathered regularly by twos and threes throughout the years. Here they were baptized, confirmed, married, buried. Through the course of evolving times, dramatic changes have taken place in the countryside, but St. Paul’s Chapel remains the same, no alterations, no additions, still painted a spotless white inside and out. There are the same pitch pine pews, but now they are bright with new varnish, and the same heavy marble baptismal font stands at the rear. There is the same lectern with the old King James Bible; the same little altar with the single stained glass window inscribed in memory of a Rev. Hugh Maycock, and a window. undated, a name unknown, but a constant reminder of someone who long ago had stood for something very sacred in the sight of God.

The only new object is a Hammond organ—lately bought.

St. Paul’s always has a country fair and farm supper in the old grove when the corn is ripe. And then they come home again, the descendants of the founding families, from far and near, to sit and chat and sup in the shade and hear the roundelay of the mocking bird.

The new rector[1] who came to Severn Parish in 1910 was a man of great talents. He had served brilliantly in a large city parish, but his days were numbered with an incurable ailment. The time he had left he devoted to the people of his new parish. Tall, emaciated, but dynamic, his sermons struck like a thunderbolt in this farm neighborhood. The churchmen soon found out he was high church as well as an evangelist for our children. He invited every child of walking age to participate in his Sunday School and vested choir. Never before had there been such a fine choir or any high church ritual in Severn Parish. And the choir was composed of boys only! He was very firm about that. This electrified the parish. Many an indifferent Episcopalian, pleasantly relaxed over church attendance, perked up and came back to long-empty seats. St. Paul’s was thrilled and proud.

There were six Charles and Brice Worthington boys. The three Maynard Carr boys. Nine! Eight to walk two by two, and one to be the cross-bearer! Fair-haired Maynard Carr was chosen for cross bearer because of his fine looks. Full-throated Benjamin Skinner Carr was made the choir leader because of his beautiful appealing voice.

The ladies of the Guild who were the mothers of the boys made the choir vestments. They were ankle-length black cassocks with white linen capes and round turned down white linen collars tied with black silk bows. The 11 A.M. Easter Sunday service was selected for the choir’s premiere at St. Paul’s. The pastor trained his boys privately behind the closed doors of the chapel. Mrs. Brice Worthington, the organist, was the only outsider present at the rehearsals.

The mothers also made new altar cloths, white satin with heavy gold fringe and gold embroidery. Even the lectern had a new white and gold “throw,” and the old Bible a new white and gold “marker.” Local flowers bedecked the altar. Most of them were daffodils, the first flowers of spring to raise their golden trumpets to the Lord.

When the congregation entered St. Paul’s that Easter morning in 1910, they saw something new on the altar. Seven candles were glowing softly among the flowers below the stained glass window!

And all through the years that followed; between the burying and the marrying and the baptizing the survivors came back to the summer festival. Here reunion and farewell are steeped with laughter and hidden tears, and memory flashes bright with unforgettable faces.

“Alleluia! Alleluia! Alleluia!”

Our minister did not die a lingering death. This ardent high churchman died with merciful suddenness in an automobile crash a few years after 1910.

And in a grim time soon after, that choir of little boys were bearing arms in World War One. Benjamin Skinner Carr never came back. Only 18 years old, he was killed in the Argonne Forest in France on the 23rd of October, 1918 while leading a a machine gun squad in action. A placque dedicated to his memory hangs in the old chapel where he sang so happily that Easter in his boyhood. He is honored by the Annapolis Carr-Saffield Post of the 115th Infantry.

And of all the mothers who listened to their sons that day, only the organist is alive in 1958, Mrs. Brice Worthington, serene in her memories of a full life, lives alone in gracious old age as 12 Maryland Avenue.

[1] The new rector mentioned here is Rev. William R. Agate.

Reflection: “And the Waters Bore Up the Ark” - Genesis 7:17 as a Foreshadow of the Cross

By Fr. Wesley Walker

This Sunday’s Old Testament reading comes from Genesis 6.

Note: This was originally published at Conciliar Post.

“The flood continued forty days on the earth; and the waters increased, and bore up the ark, and it rose high above the earth.”

-Genesis 7:17 (NRSV)

Recently, I had occasion to complain to a friend about the elasticity of the word “literal” when wielded in discussions concerning hermeneutics. The word is frequently used as a placeholder for vapid personal interpretations derived in absentia of authorial intent, historical context, and the traditions of the Church. Medieval biblical exegete Nicholas of Lyra (1270-1349) argued for the duplex sensus literalis (“double-literal sense”) of the Bible. This view allows readers of Scripture to engage the text on the literal-historical level while also allowing for engagement on a prophetic level that makes room for a typological reading which sees the real, historical events recorded in Scripture as pointing to a grander, ultimate Reality (see Levy, Introducing Medieval Biblical Interpretation: The Senses of Scripture in Premodern Exegesis, 281-5). This helpful hermeneutic can guide us to encounter Scripture in a deeper, more canonical way. One fascinating example of the duplex sensus literalis is Genesis 7:17.

Genesis 7:17 details the great flood and the ark being lifted up by the waters. On a literal-historical level (however you might apply that term to what occurs in Genesis 1-11), this describes the magnitude of the flood, emphasizing the height of the ark above the earth because of the destructive waters. The Greek verb for “bore up” in the LXX is ύψοω (hypsoo). This is the same Greek word used in John 3:14-15, “And just as Moses lifted up the serpent in the wilderness, so must the Son of Man be lifted up, that whoever believes in him may have eternal life” and John 12:32, “And I, when I am lifted up from the earth, will draw all people to myself.” (emphasis added).

From the beginning, Christians have seen parallels between Noah’s Ark and Christ. 1 Peter 3:18b-21 uses the Ark as a parallel to Christ’s work and the sacrament of Baptism:

“He was put to death in the flesh, but made alive in the spirit, in which also he went and made a proclamation to the spirits in prison, who in former times did not obey, when God waited patiently in the days of Noah, during the building of the ark, in which a few, that is, eight persons, were saved through water. And baptism, which this prefigured, now saves you—not as a removal of dirt from the body, but as an appeal to God for a good conscience, through the resurrection of Jesus Christ.”

Christians took this to heart; it even influenced the architecture of churches. The central part of the church building became known as the nave which is a derivative of navis, a Latin word meaning “boat.” They did this because they understood that the Church, the institution established by Christ, to be an Ark which was keeping them safe from the destruction of sin in the outside world.

Augustine advanced his interpretation of Noah and the flood still further, even making use of the dimensions of the structure of the Ark as recorded in Scripture (Contra Faustum, XII, 14):

“Noah, with his family is saved by water and wood, as the family of Christ is saved by baptism, as representing the suffering of the cross. That this ark is made of beams formed in a square, as the Church is constructed of saints prepared unto every good work: for a square stands firm on any side. That the length is six times the breadth, and ten times the height, like a human body, to show that Christ appeared in a human body. That the breadth reaches to fifty cubits; as the apostle says, ‘Our heart is enlarged,’ (2 Cor 6:11) that is, with spiritual love, of which he says again, ‘The love of God is shed abroad in our heart by the Holy Ghost, which is given unto us’ (Rom 5:5). For in the fiftieth day after His resurrection, Christ sent His Holy Spirit to enlarge the hearts of His disciples. That it is three hundred cubits long, to make up six times fifty; as there are six periods in the history of the world during which Christ has never ceased to be preached — in five foretold by the prophets, and in the sixth proclaimed in the gospel. That it is thirty cubits high, a tenth part of the length; because Christ is our height, who in his thirtieth year gave His sanction to the doctrine of the gospel, by declaring that He came not to destroy the law, but to fulfil it. Now the ten commandments are to be the heart of the law; and so the length of the ark is ten times thirty. Noah himself, too, was the tenth from Adam. That the beams of the ark are fastened within and without with pitch, to signify by compact union the forbearance of love, which keeps the brotherly connection from being impaired, and the bond of peace from being broken by the offenses which try the Church either from without or from within. For pitch is a glutinous substance, of great energy and force, to represent the ardor of love which, with great power of endurance, bears all things in the maintenance of spiritual communion.”

In light of these connections, Genesis 7:17’s parallels with John 3:14-15 and 12:32 are all the more interesting. The Ark anticipates the lifting up of Christ on the cross.

What is the significance of the connection between the Ark and the crucifixion of Christ? St. Athanasius’ book On the Incarnation is helpful in answering this question. Explaining why Christ died the exact way he did, Athanasius makes some wonderful points about symbolism. He explains that Christ died the way he did because he had to be killed by enemies in public with witnesses (53-4). According to Athanasius, he was specifically crucified for two reasons. First, in crucifixion his arms were outstretched “that He might draw His ancient people with the one and the Gentiles with the other” (55). The other reason, which he connects to John 12:32, is that Christ had to be lifted up because: “the air is the sphere of the devil, the enemy of our race.” The devil, fallen from heaven:

“Endeavours with the other evil spirits who shared in his disobedience both to keep souls from the truth and to hinder the progress of those who are trying to follow it…the Lord came to overthrew the devil and to purify the air and to make ‘a way’ for us up to heaven, as the apostle says, ‘through the veil, that is to say, His flesh.’ He cleansed the air from all the evil influences of the enemy.” (55)

The cross is a symbol of Christus victor because, even in his death, Christ purges the air (Eph 2:2) from Satan’s influence, ultimately causing the defeat of Sin and Death.

Understanding the duplex sensus literalis can aid readers of Scripture in seeing the patterns and rhythms of God on display, as he continuously intervenes in time and space. Nothing in Scripture is there by accident. The Bible is not a haphazardly compiled collection. Much like an artist uses similar strokes, colors, subjects, lighting, etc. in their work, so God used and continues to use discernible types and figures to bring about the salvation of all things (2 Cor 5:19). As we encounter these types, we can expect them to point to Christ (Col 2:17). The Ark is no exception. Noah and his family were saved by being on the inside of the Ark as the flood waters purged the earth of life. Likewise, those who find themselves in Christ will be saved from their sins. In both the lifting up of the Ark and the lifting up of the Son of Man, God is glorified because of his salvific actions on behalf of his Creation.

Old Time Bible Hour: This Tuesday at 7p

The Old Time Bible Hour is a monthly study where we explore how Christians who have gone before us read the Scriptures. This month, we will be reading and discussing Hugh of Saint Victor’s interpretation of Isaiah 6 and Noah’s Ark.

Evening Prayer will be said at 6:30p.

You can download the reading here or email Fr. Wesley at wwalker@stpaulscrownsville.com.

Fall 23-Spring 24 Friday Study: The Divine Comedy

The Divine Comedy is one of the most magnificent epic poems in the canon of Western Literature. In it, Dante Alighieri will take us on a journey set in the realms of the afterlife that serve as a backdrop to explore the human condition, theology, and beatitude. The Divine Comedy is divided into three parts, Inferno, Purgatorio, and Paradiso. We will delve into the depths of Hell with Dante and his guide, Virgil; we will climb Mount Purgatory with them; and we will explore the glorious realms of heaven. Dante’s writing, which makes heavy use of symbolism, allegory, and moral teaching, will make us confront important realities like sin, justice, and divine mercy. This is a truly timeless work that still captivates and inspires many with its profound insights into the human soul and the eternal pursuit of truth and salvation. The study will range from August 25-May 3.

Bibliography of Recommended Resources

Recommended Translation: Dante. The Divine Comedy: Inferno, Purgatorio, Paradiso. Everyman’s Library 183. Translated by Allen Mandelbaum. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1995. ISBN: 978-09-679-43313-2.

100 Days of Dante by Baylor University. https://100daysofdante.com/

Baxter, Jason M. A Beginner’s Guide to Dante’s Divine Comedy. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2018. ISBN: 978-0801098734.

Leithart, Peter J. Ascent to Love: A Guide to Dante’s Divine Comedy. Moscow, ID: Canon Press, 2001. ISBN: 978-1885767165.