NEWS

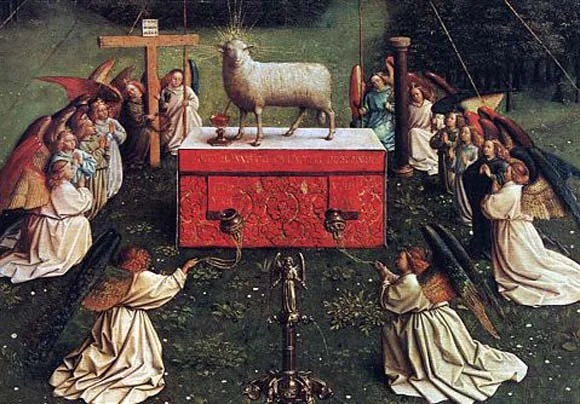

“Thusia Eucharistikon: The Eucharistic Sacrifice” By Bp. Chandler Holder Jones

Dear APA Clergy, Deaconesses, and Other Retreat Participants,

We had several requests for a written copy of Bishop Chad's teaching on The Eucharistic Sacrifice in Anglicanism given at the retreat sessions. Attached is a copy (minus Q&As) for your reference and enlightenment.

The Plan for This Sunday

Dear St. Paul’s,

Given the burst pipe issue and the damage that resulted in the upstairs sanctuary, fellowship hall, and nursery, we’re going to have to adapt over the coming weeks.

Here are some details about Sunday.

Services:

We will continue having three services on Sunday at 8a, 9:30a, and 11a. All three services will be Holy Communion and will take place in the chapel.

If you attend 11a, please consider attending the 8a or 9:30a service. Because seating is limited in the chapel, we need people to distribute themselves across the different services.

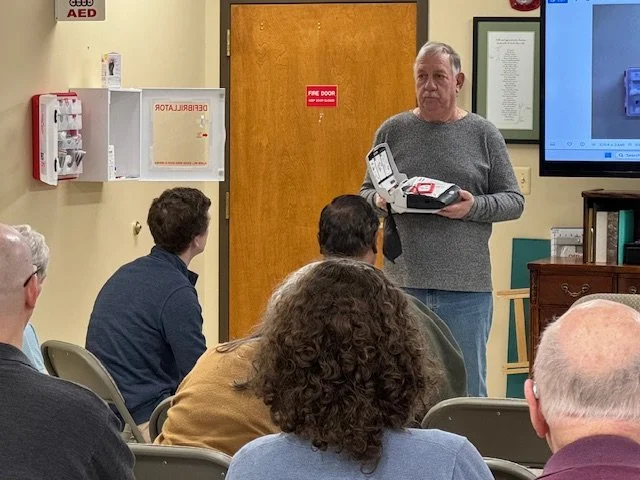

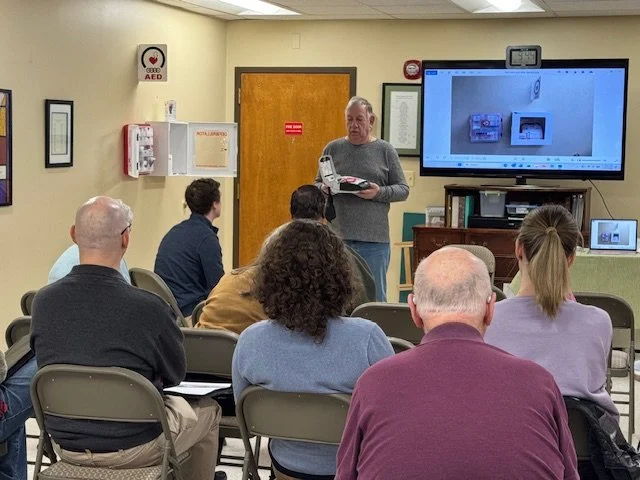

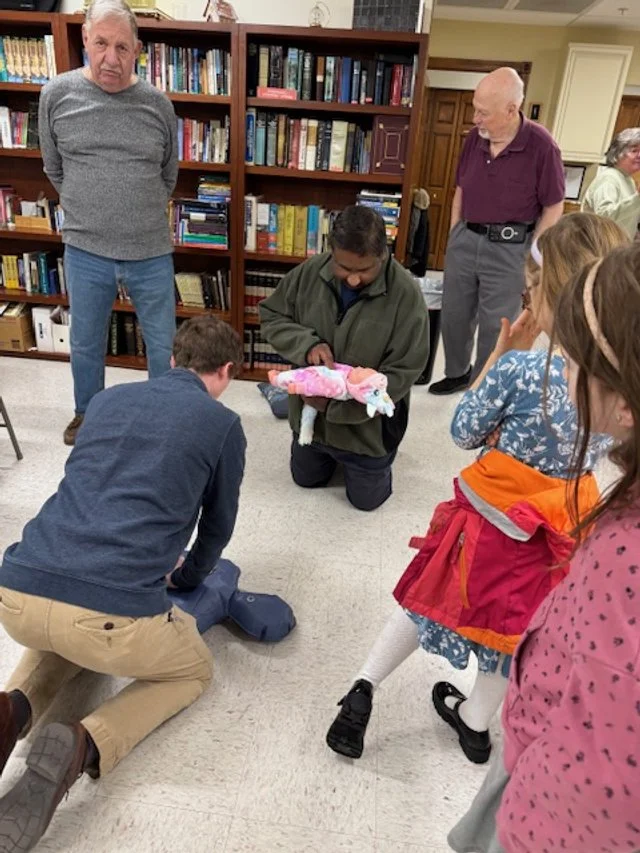

Nursery:

Sadly, we will not be able to offer nursery care due to the current state of the nursery. Nursery care will resume at a later date. Children are welcome in the service.

Coffee Hour:

We will forego coffee hour this week due to the state of the fellowship hall. We are optimistic that the fellowship hall will be restored to use for Shrove Tuesday.

As we move forward, we’ll have more information by way of what the parish needs in order to get the sanctuary and nave upstairs back in working condition.

If you have any questions moving forward, please don’t hesitate to send me an email or give me a call!

Blessings,

Fr. Wesley

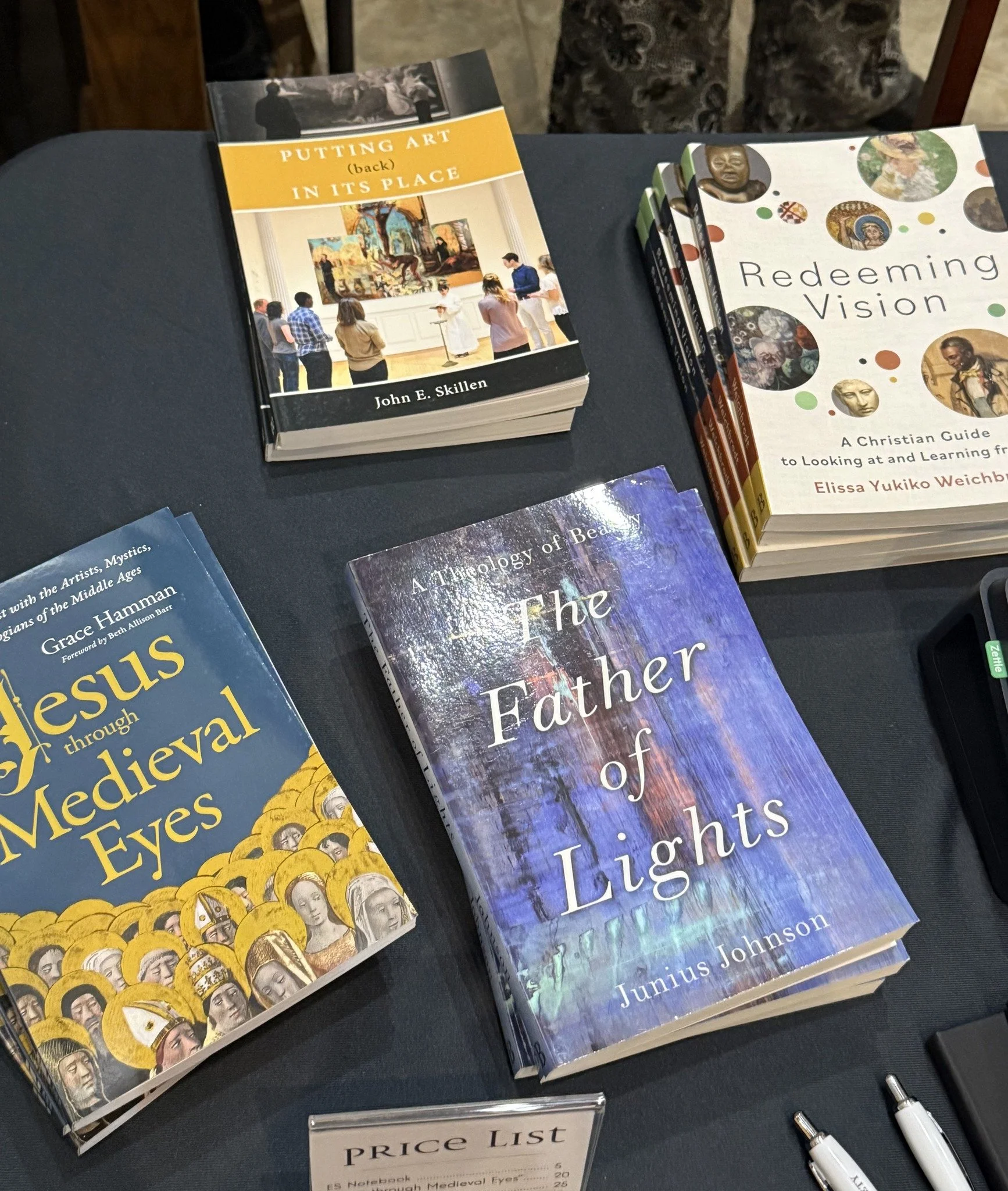

Resources for a Holier Lent

By Fr. Wesley Walker

It always helps to have a guide. Dante needed Virgil to get through hell and purgatory, Frodo needed Gandalf to get to Moria, Merlin had to advise Arthur, the three Christmas ghosts guided Scrooge into becoming human again. As we are about to embark on an epic journey of our own in the forty days of Lent, we may find the quest more navigable if we choose a wise guide to help us reach our Paschal destination. To this end, below are ten resources that have acted as a guide in my own life that I would recommend to anyone who is looking for a guide of their own. It’s not an exhaustive list, but it is a start.

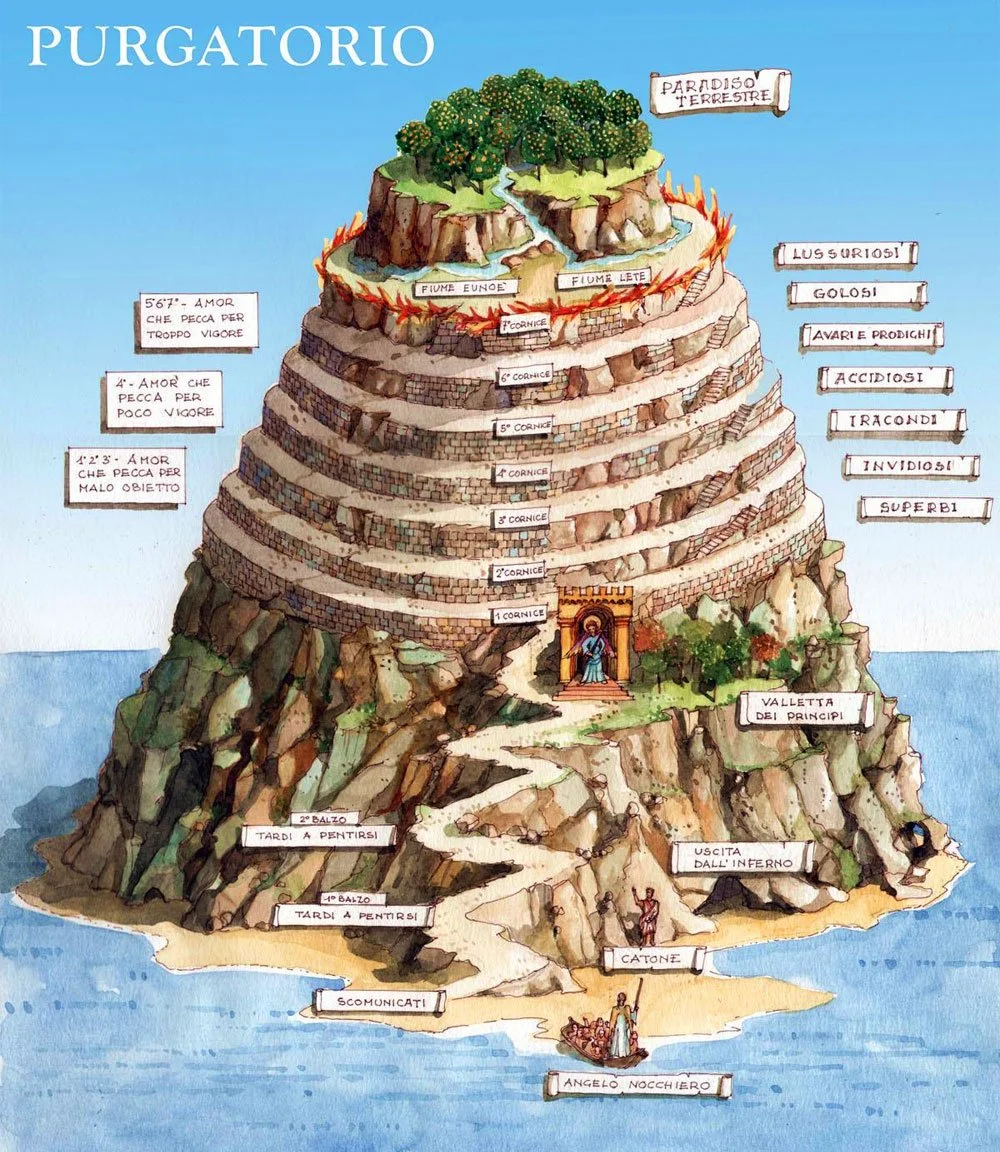

Purgatorio by Dante

All of the Divine Comedy is worth reading. However the best and most relevant portion of the trilogy is Purgatorio.

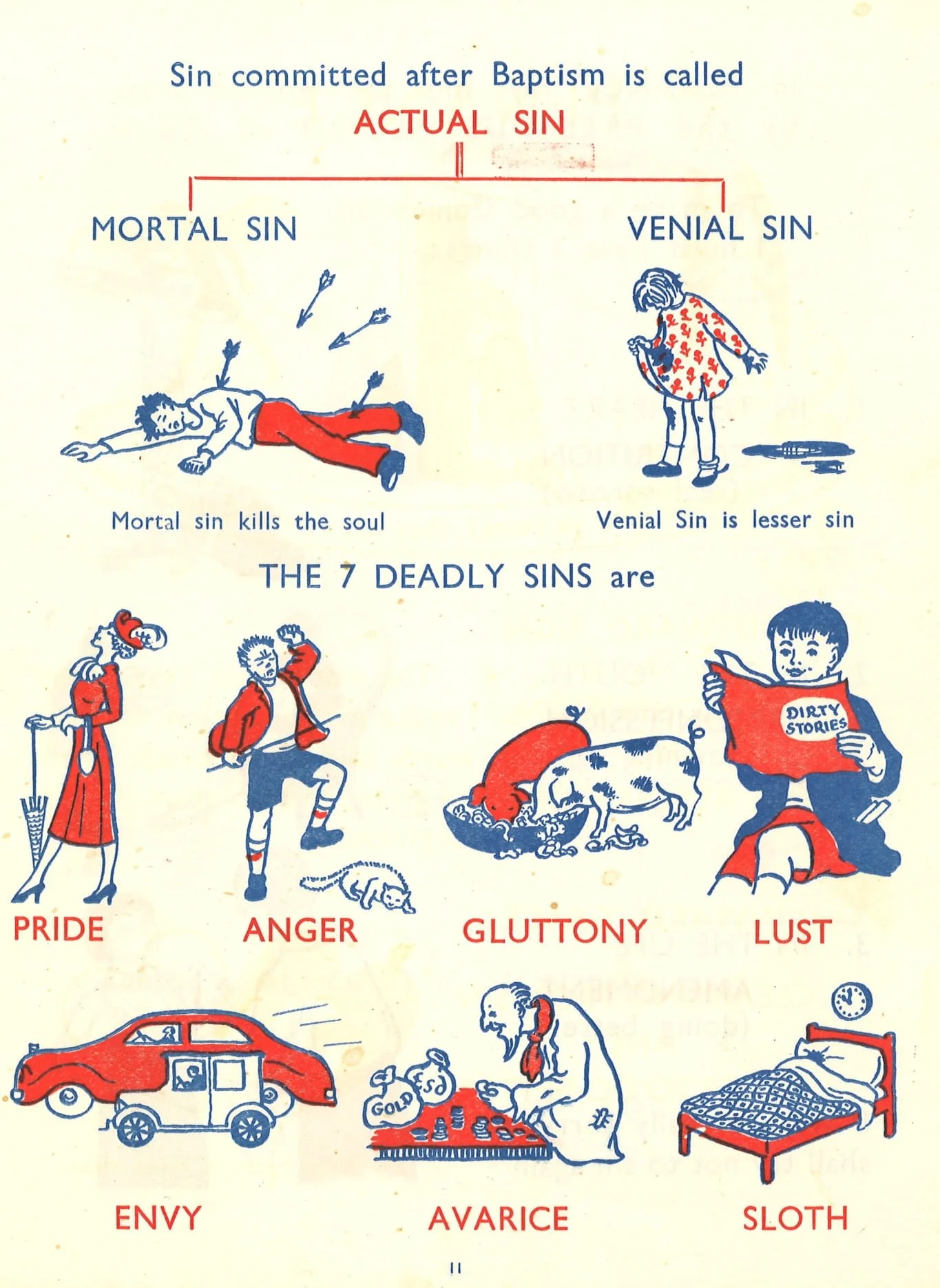

After Dante descends through the circles of hell and observes its many horrors, he arrives on the beaches of Mount Purgatory. The souls in Purgatory are “saved” in that their final destination of heaven is assured, but they have to be purified of the seven deadly sins first.

The Christian life is one of purgation of vice and acquisition of virtue. This should be the thrust of our whole lives but especially during Lent. Having depicted the sufferings of hell, Dante invites us to a better way, a more human way.

If the prospect of journeying alongside Dante is overwhelming, considering a guide to guide you through it. A Beginner’s Guide to Dante’s Divine Comedy by Jason M. Baxter is an excellent choice.

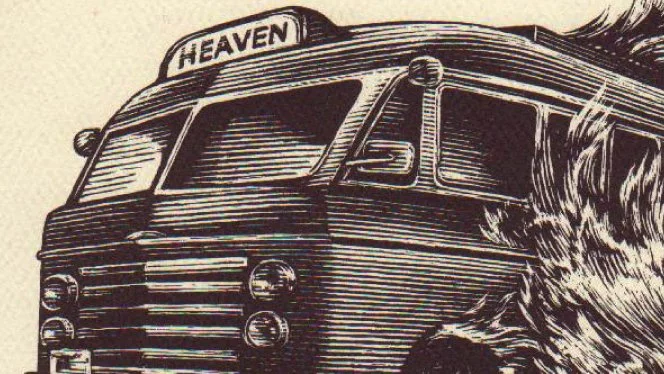

The Great Divorce by C.S. Lewis

What if the residents of hell could, at any point, take a bus ride out and get to heaven? What would need to change about them to be able to stay in paradise? Would they even want to be there at all? These are some of the many questions explored by C.S. Lewis in his short but dense classic that I like to call “diet Dante.” It pairs well with the Divine Comedy but it also condenses many of the same themes and makes them more accessible.

Malcolm Guite is an Anglican poet, priest, and academic. The Word in the Wilderness features a poem selected by Guide for each day in Lent and includes some devotional commentary on it. It’s a great book for anyone, but especially someone who wants to read more poetry but may not know where to start.

Here’s a preview of the content, Guite’s own poem for Ash Wednesday:

Receive this cross of ash upon your brow

Brought from the burning of Palm Sunday’s cross;

The forests of the world are burning now

And you make late repentance for the loss.

But all the trees of God would clap their hands,

The very stones themselves would shout and sing,

If you could covenant to love these lands

And recognize in Christ their lord and king.

He sees the slow destruction of those trees,

He weeps to see the ancient places burn,

And still you make what purchases you please

And still to dust and ashes you return.

But Hope could rise from ashes even now

Beginning with this sign upon your brow.

Lilith by George MacDonald

Lilith by George MacDonald—the literary mentor of C.S. Lewis—is a fantasy novel in which a man from our world is drawn into a parallel universe by a Raven. In this other world, he encounters many fantastical things, including Lilith, who, according to some Jewish tradition, was Adam’s original wife before she was seduced by evil and fell before the creation of Eve. The story is about the redemption of the cosmos and deals with themes of death, judgment, and reconciliation, all of which are pertinent for the Lenten season.

I recently had the privilege of discussing this novel with my friend, Junius Johnson. You can watch that video below if you’re interested:

Christian Proficiency by Martin Thornton

In a recent sermon, I mentioned the Pre-Lent and Lent are seasons that center on training us in the disciplines of the Christian life. Martin Thornton was an Anglican priest and ascetical theologian whose work can help us better acquire those disciplines as we have received them in the Anglican tradition.

The Book of Common Prayer, he argues, is an ascetical system; it structures our prayer life. What is the shape of that prayer life? According to the BCP, it’s weekly Holy Communion, daily Morning and Evening Prayer, and a robust private prayer life developed in consultation with a spiritual director.

We have done some work on Thornton and the rule here at St. Paul’s. Below are some resources that might be helpful whether you’re interested in reading Christian Proficiency this Lent or not”

Rule of Prayer: Session 2 - The Threefold Cord: Mass, Daily Office, and Prayer

Rule of Prayer: Session 3 - Spiritual Direction: Implementing the Rule

The Daily Office Workshop that we hosted in March 2024 which focuses on how to pray Morning and Evening Prayer

Jesus of Nazareth: Holy Week: From the Entrance into Jerusalem to the Resurrection by Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger (Pope Benedict XVI)

At the beginning of Lent, we join our Lord in setting our faces towards Jerusalem. The Lenten season culminates during the events of Holy Week: Palm Sunday, Maundy Thursday, Good Friday, and Holy Saturday. Ratzinger is a terrific guide through these events as he engages the biblical text from the great Western theological tradition. He will have you thinking about Holy Week in new (but really old) ways.

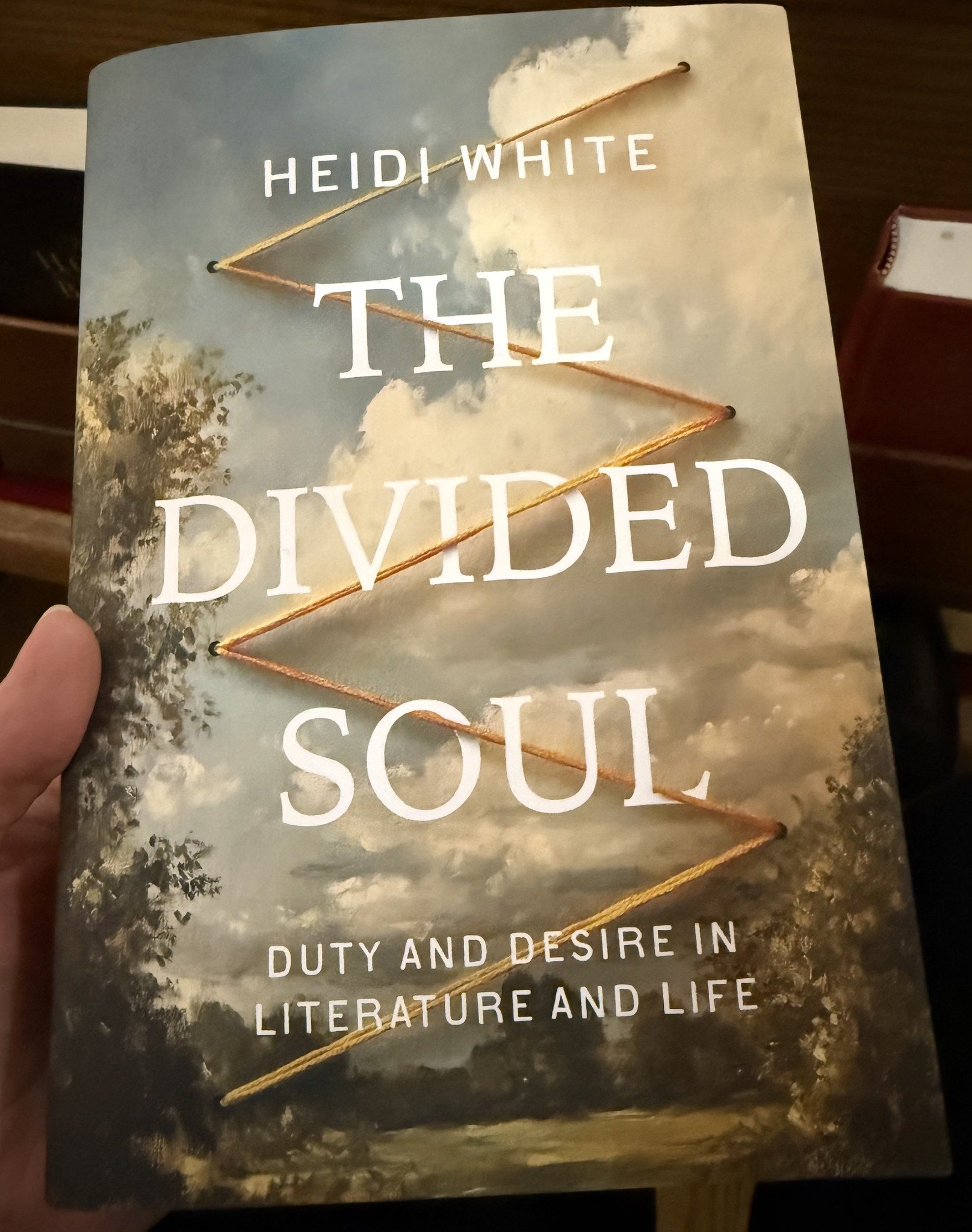

The Divided Soul: Duty and Desire in Literature and Life by Heidi White

Heidi White gave a wonderful talk at St. Paul’s through the Eliot Society. Her central thesis is that all literature revolves around two poles: desire and duty. She traces this back to the story of the prodigal son: the prodigal represents desire and the elder brother represents duty.

Before sin, Adam and Eve would have experienced a harmony between duty and desire. They knew what they should do and they wanted to do it. Sin disintegrates the human person and pits our duties and desires against one another.

Part of the discipline of Lenten fasting is that we learn to control our passions and to bring our desire back into harmony with our duty. By drawing from literature White can further help us as we become more united with ourselves.

Note: you cannot buy her book on Amazon; it can be purchased at Goldberry Press here.

The Noonday Devil: Acedia, the Unnamed Evil of Our Times by Jean-Charles Nault

Acedia is the most pervasive sin you’ve never heard of. It has been defined a few different ways throughout Church history. Evagrius of Pontus tells us that acedia is a spiritual lack of care, the “temptation to withdraw from the narrowness of the present so as to take refuge in what is imaginary; it is the temptation to quit the battle so as to become a simple spectator of the controversy that is unfolding in the world” (135). Thomas Aquinas defines acedia as sadness about a spiritual good and a disgust with activity.

Nault contends that acedia has created a major crisis in the Church. To help us remedy acedia, we need the medicine of joyful perseverance, to be faithful in the little things, to meditate on Scripture, to remember death. and to focus on the Incarnation.

Images of Pilgrimage: Paradise and Wilderness in Christian Spirituality by Robert Crouse

Lent begins in the wilderness. The first Sunday in Lent’s Gospel reading details Jesus’ 40 days in the wilderness which acts as the template for our Lenten fast. But just like Israel entered the Promise Land after 40 years of wandering, our Lenten journey will terminate in the Paschal celebration.

Robert Course, an Anglican priest and theologian, offers reflections for those of us who are making the journey from the wilderness of the world to Paradise. He frequently engages with Dante and Augustine.

I wrote more about this book previously in “From the Rector’s Bookshelf: Images of Pilgrimage by R.D. Crouse”.

Sermons for Lent and the Easter Season by Bernard of Clairvaux

St. Bernard of Clairvaux lived from 1090 until 1153. He was a Cistercian monk and was known for his preaching.

These sermons are a wonderful way to think and pray through Lent!

The Bulletin for the Live Stream of Morning Prayer on Septaugesima Sunday (February 1, 2026)

DUE TO CONTINUED ISSUES WITH ICE AND INCLEMENT WEATHER, WE WILL BE OPERATING ON AN ADJUSTED SCHEDULE THIS WEEKEND:

The 8a service will be canceled

The 9:30a service will be live-streamed on the parish Facebook page

The 11a service will be in-person with no choir and no coffee hour following the service. Parking will be limited due to ice coverage of the parking lot.

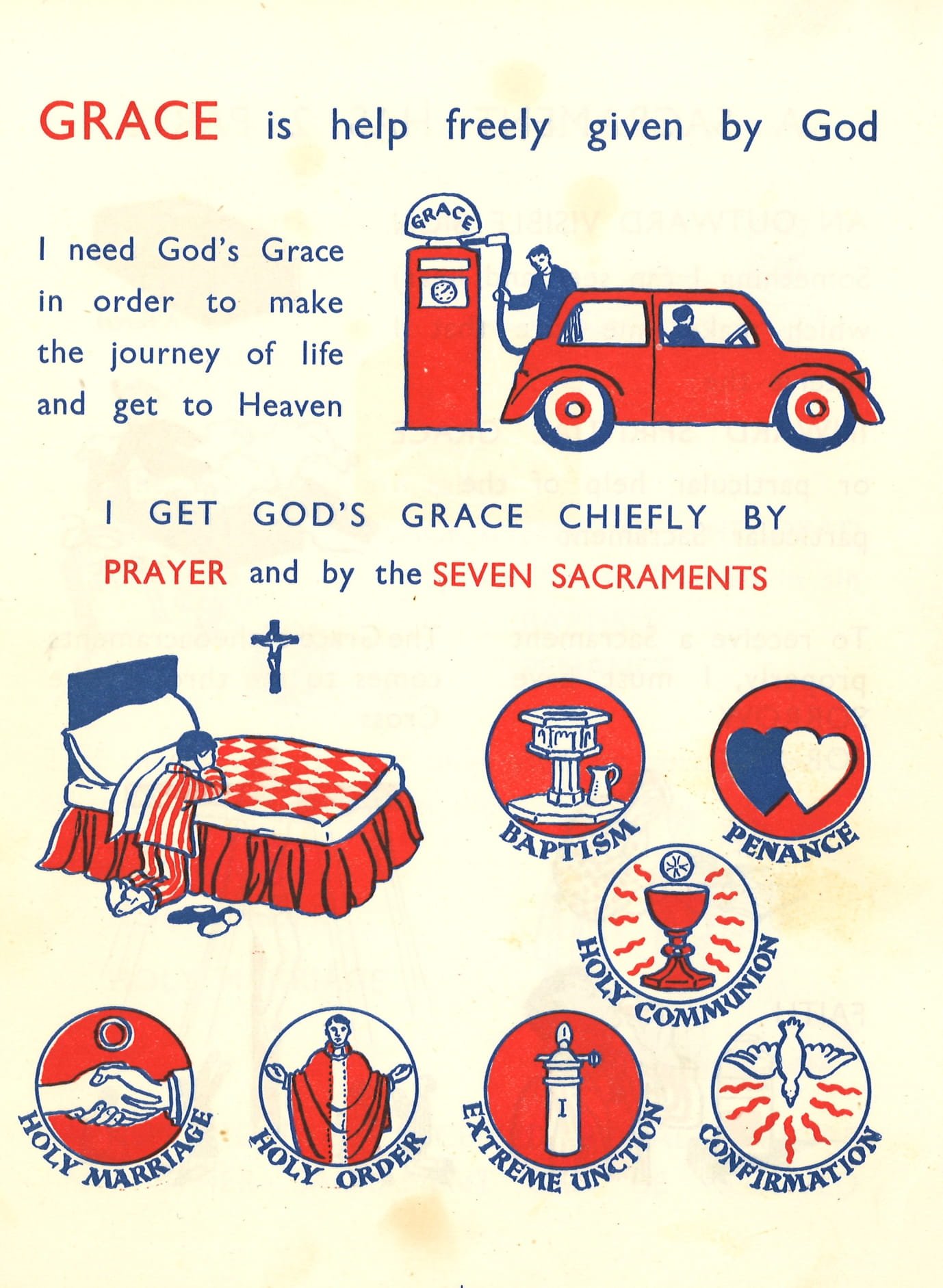

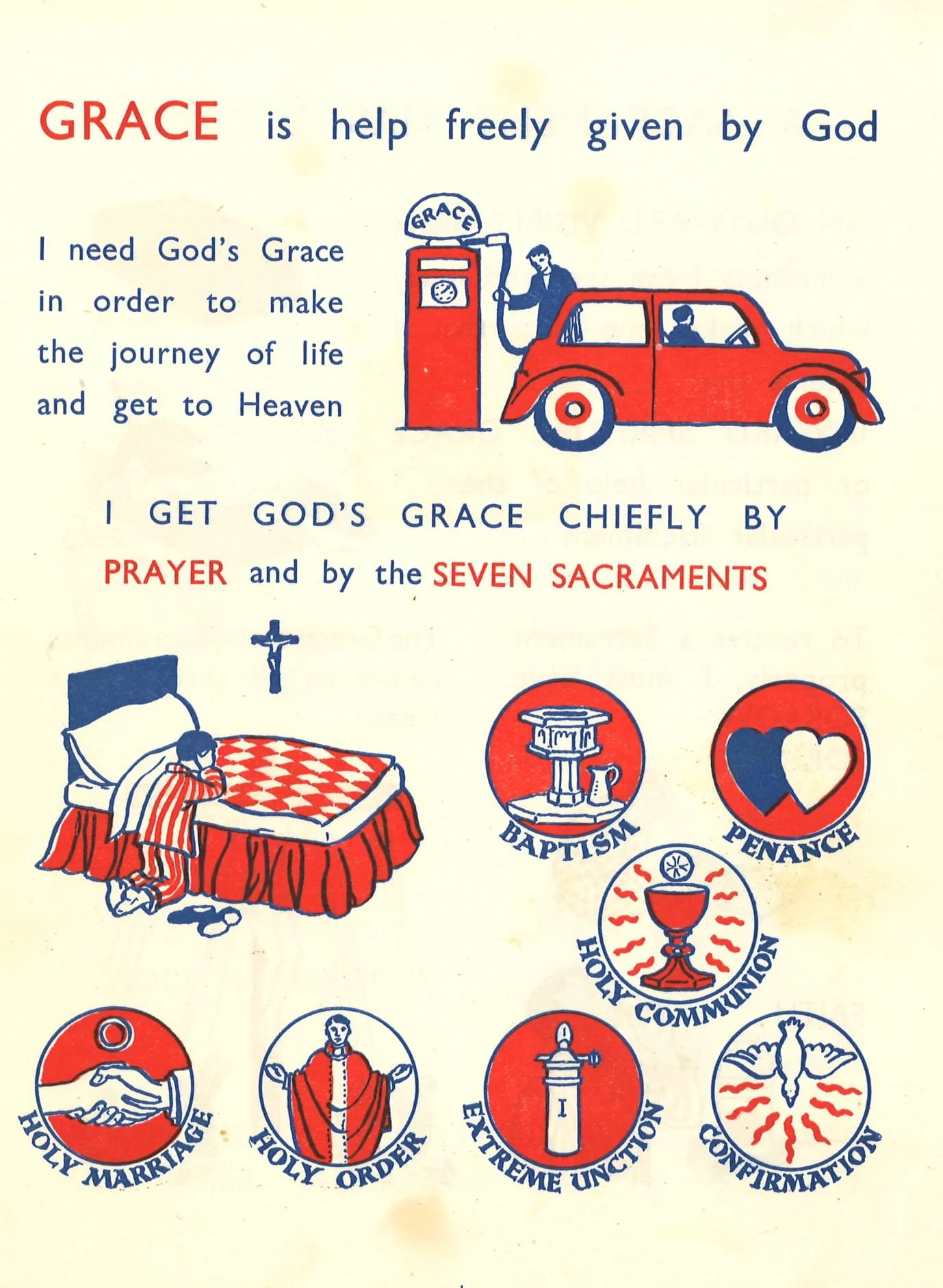

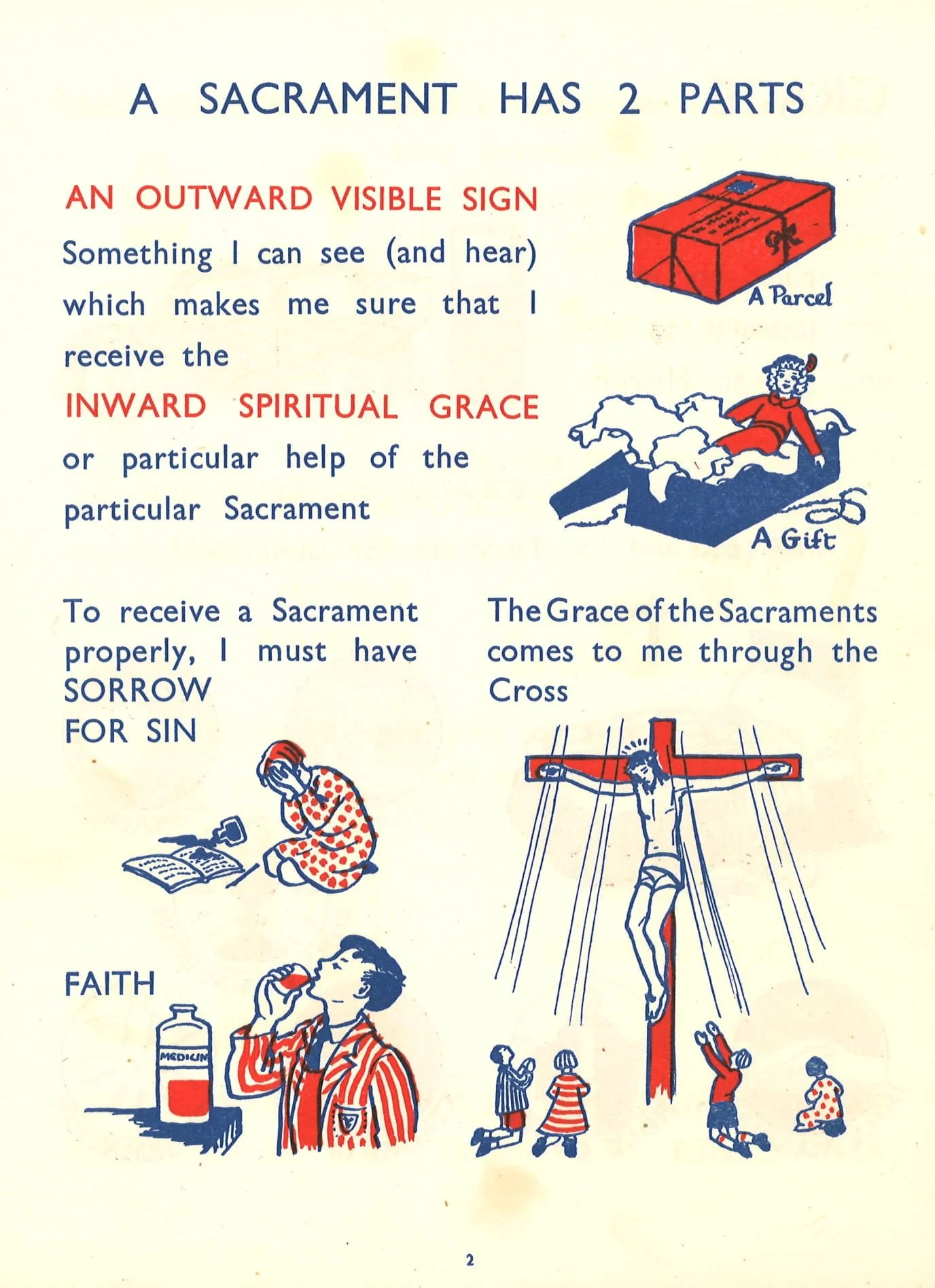

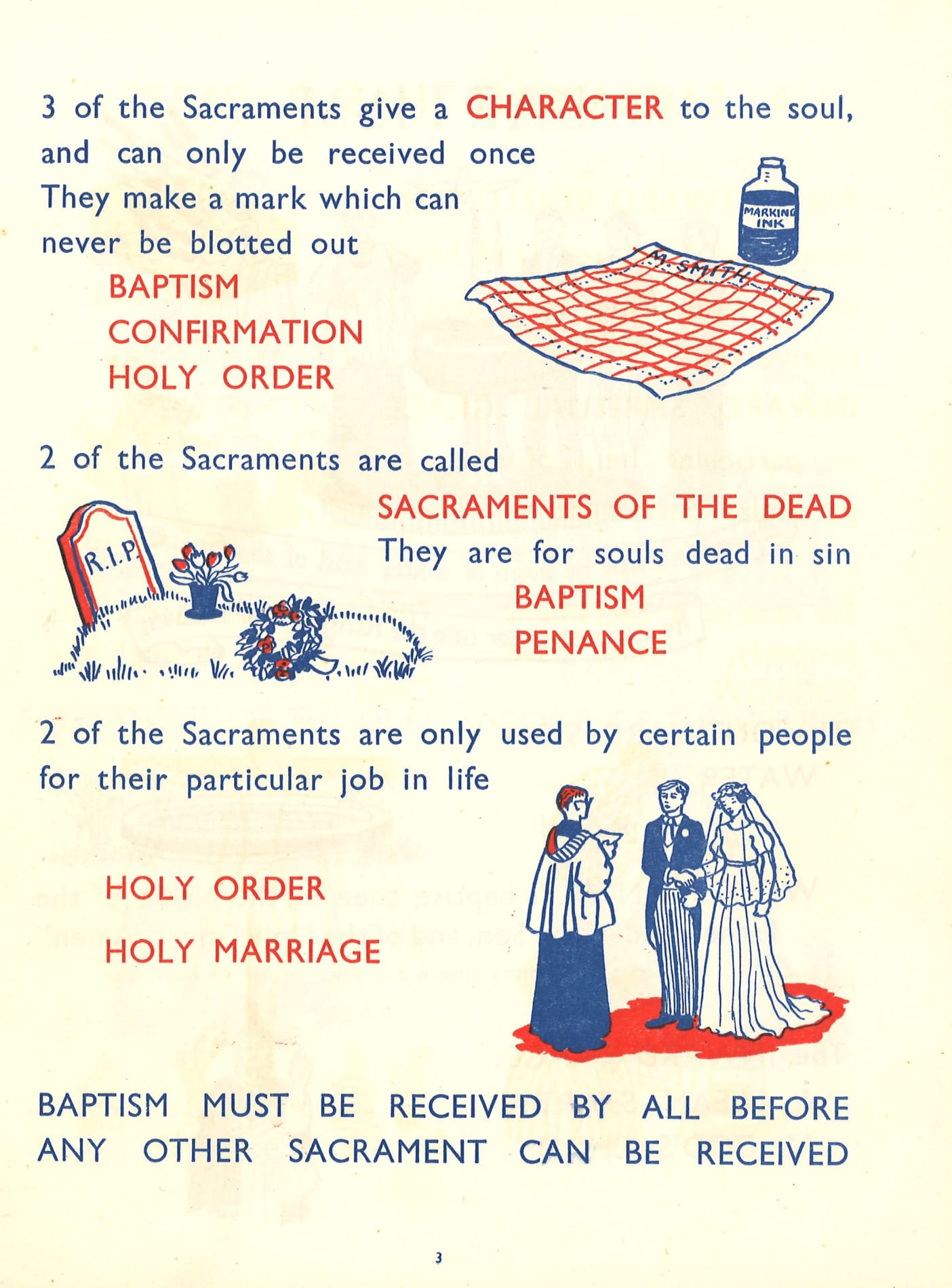

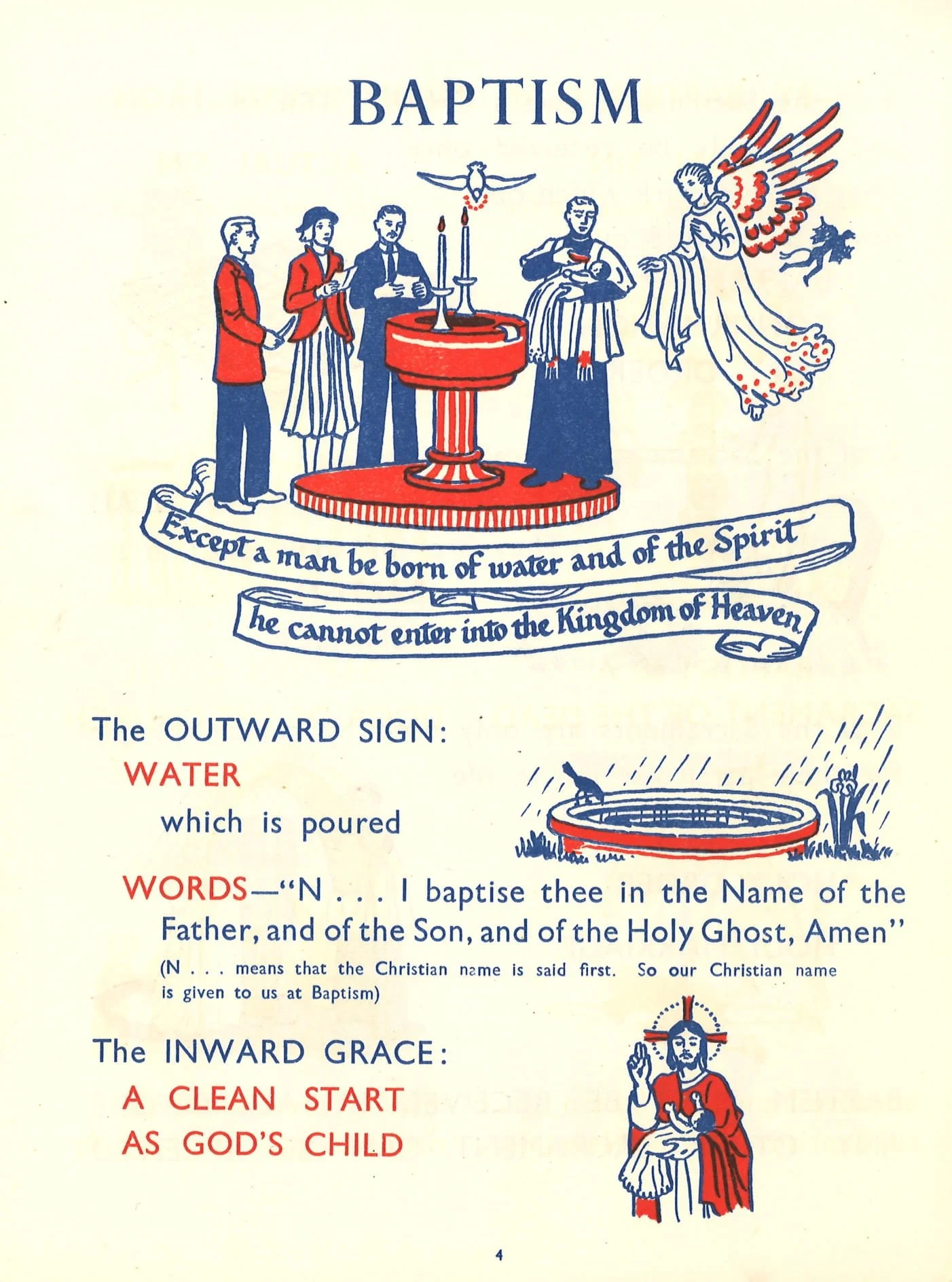

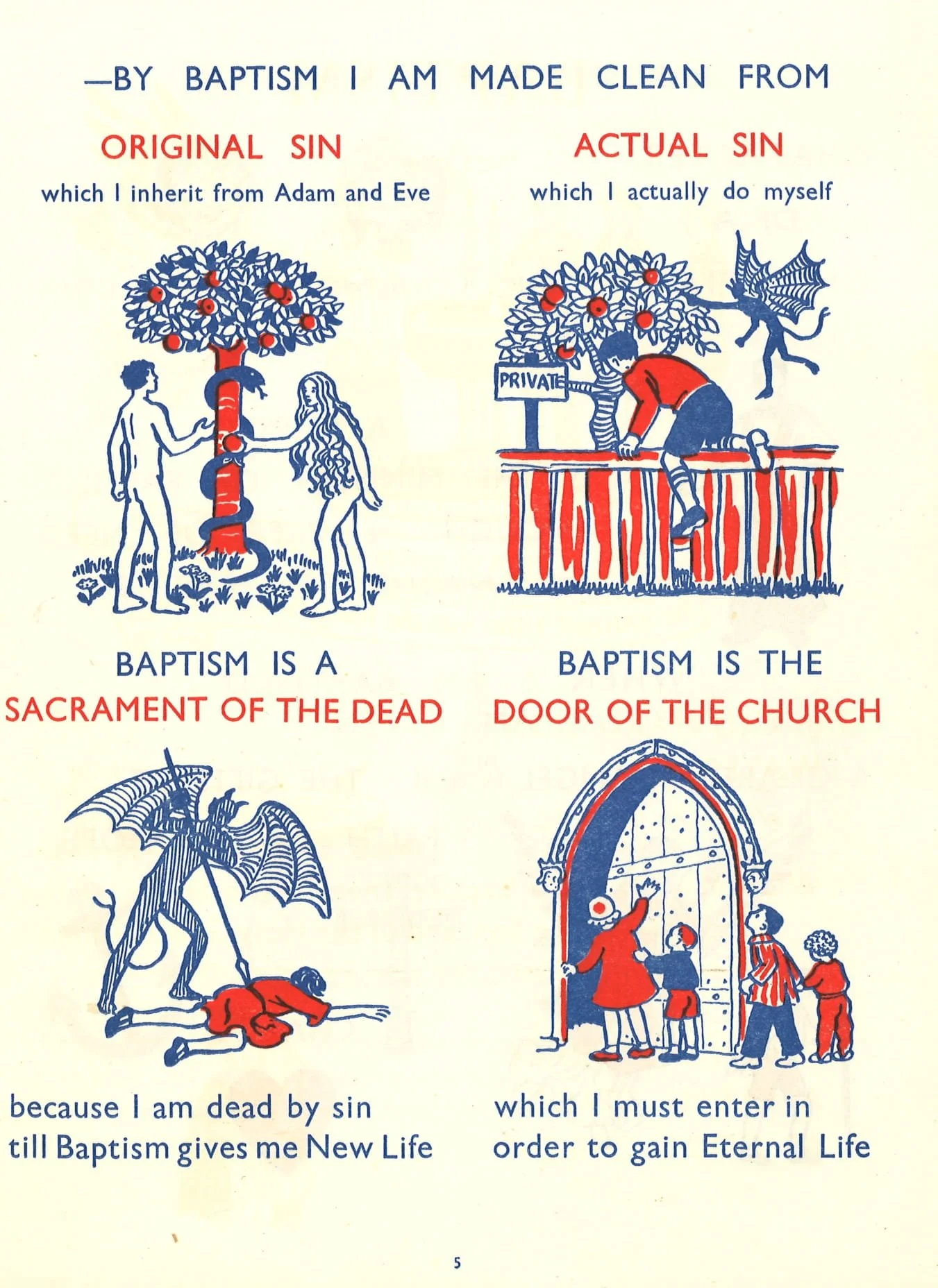

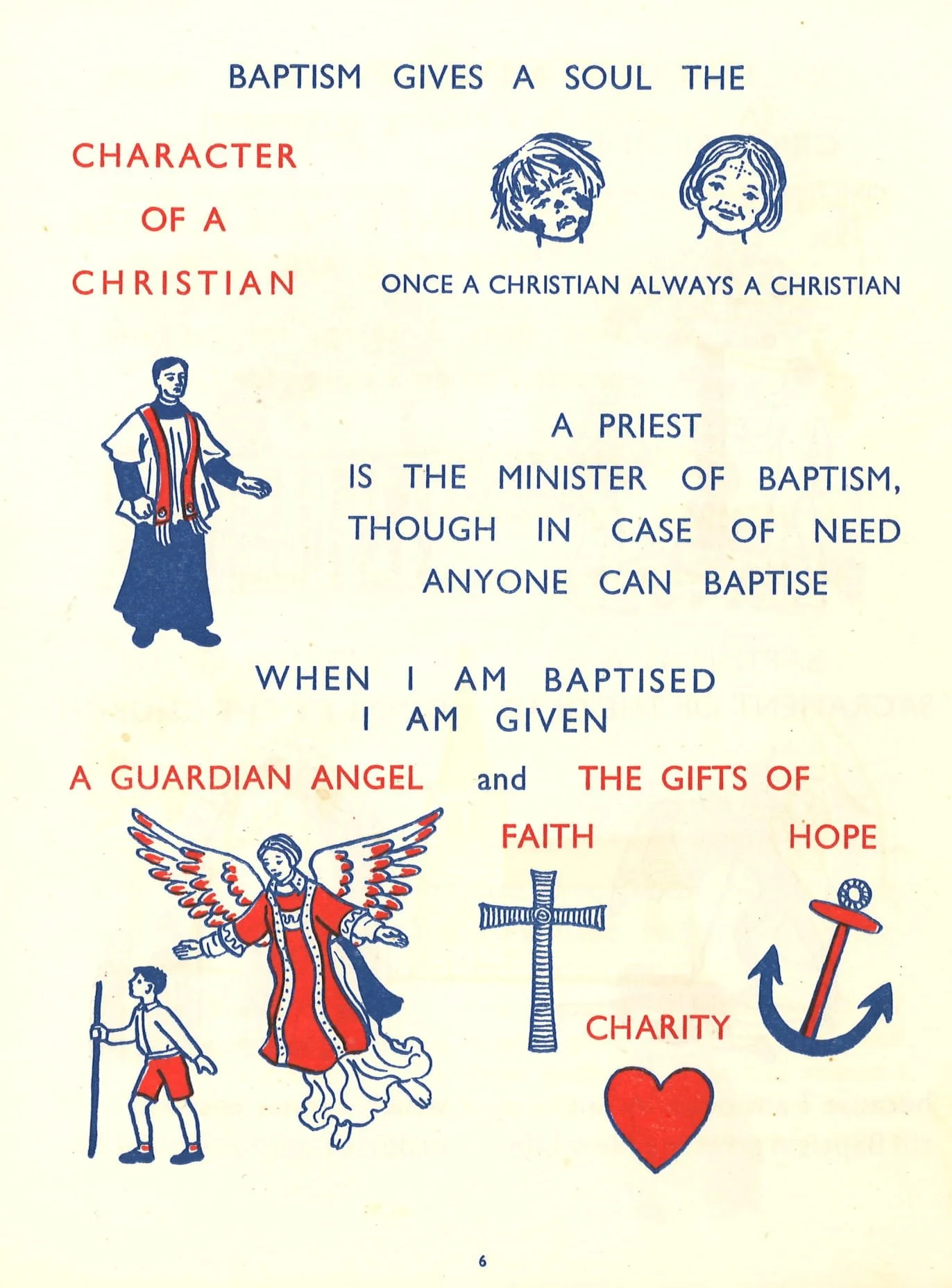

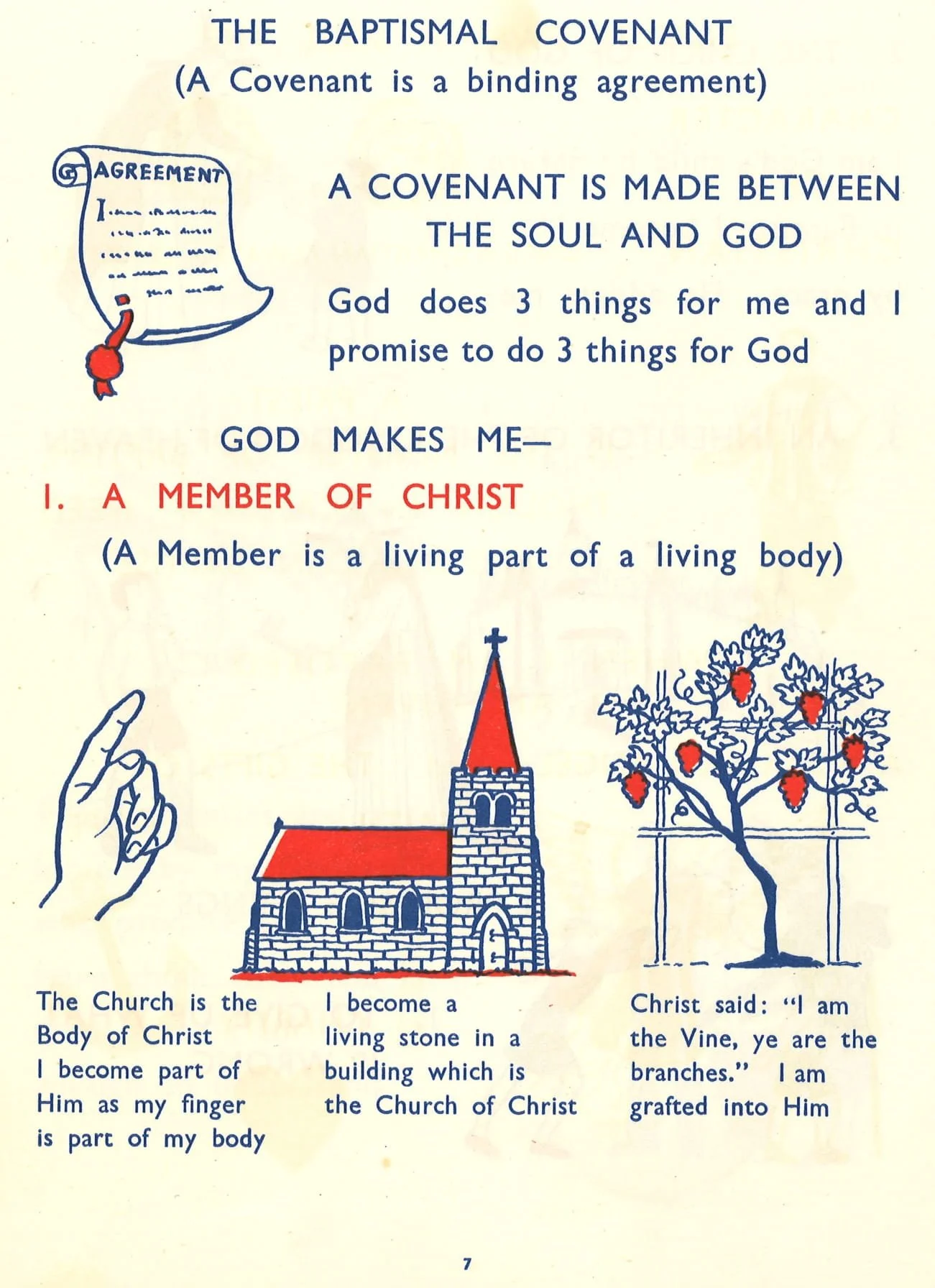

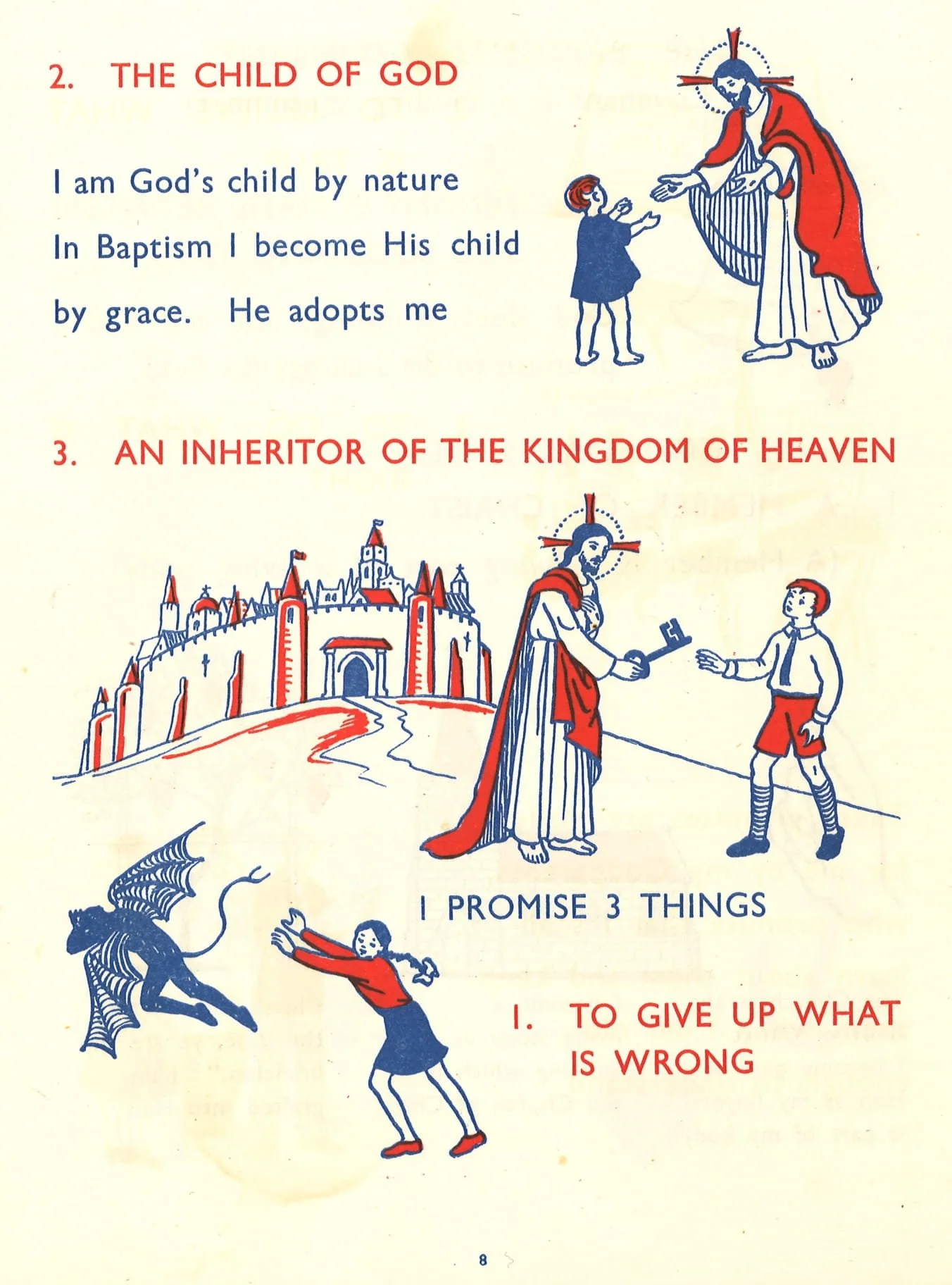

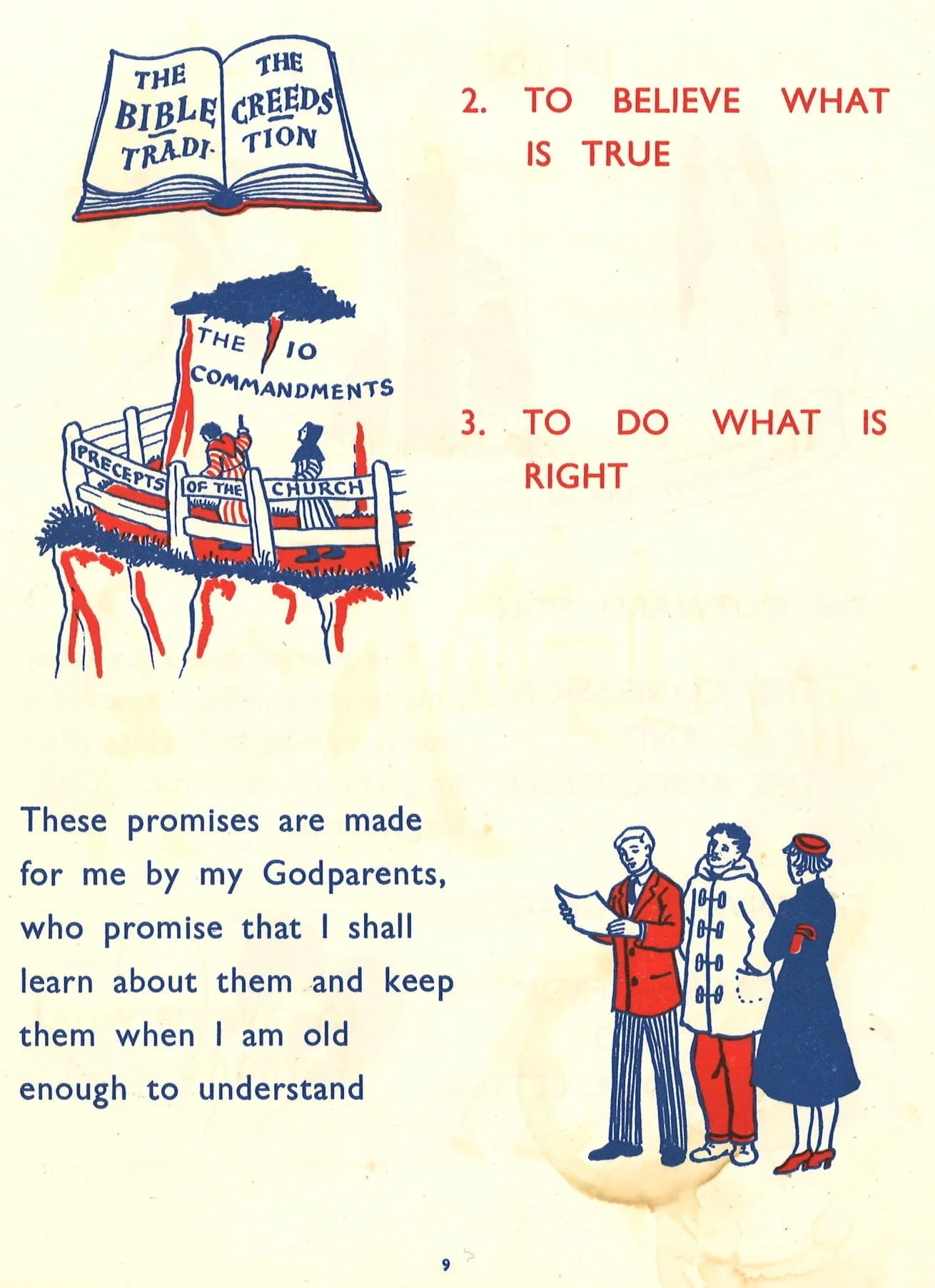

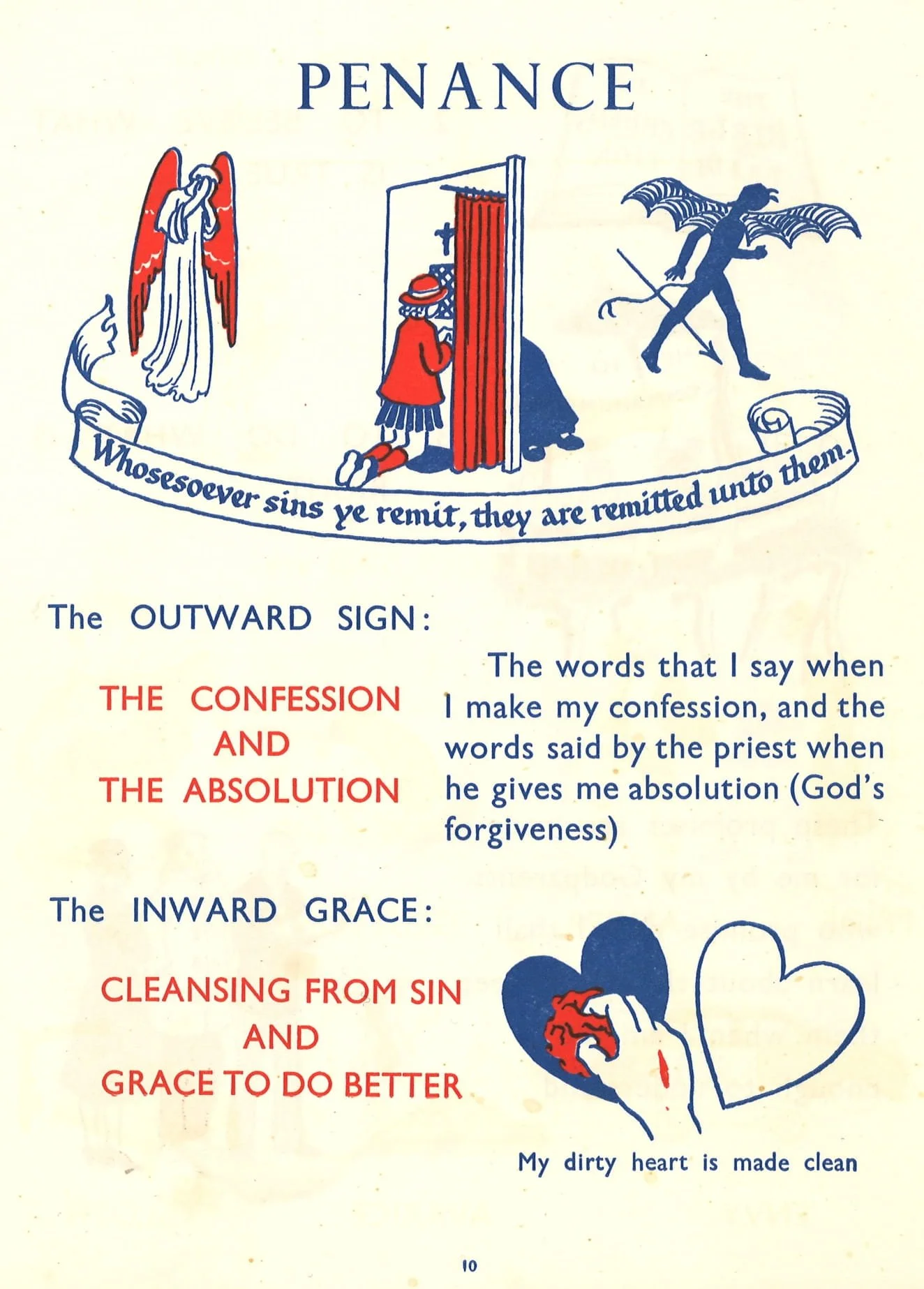

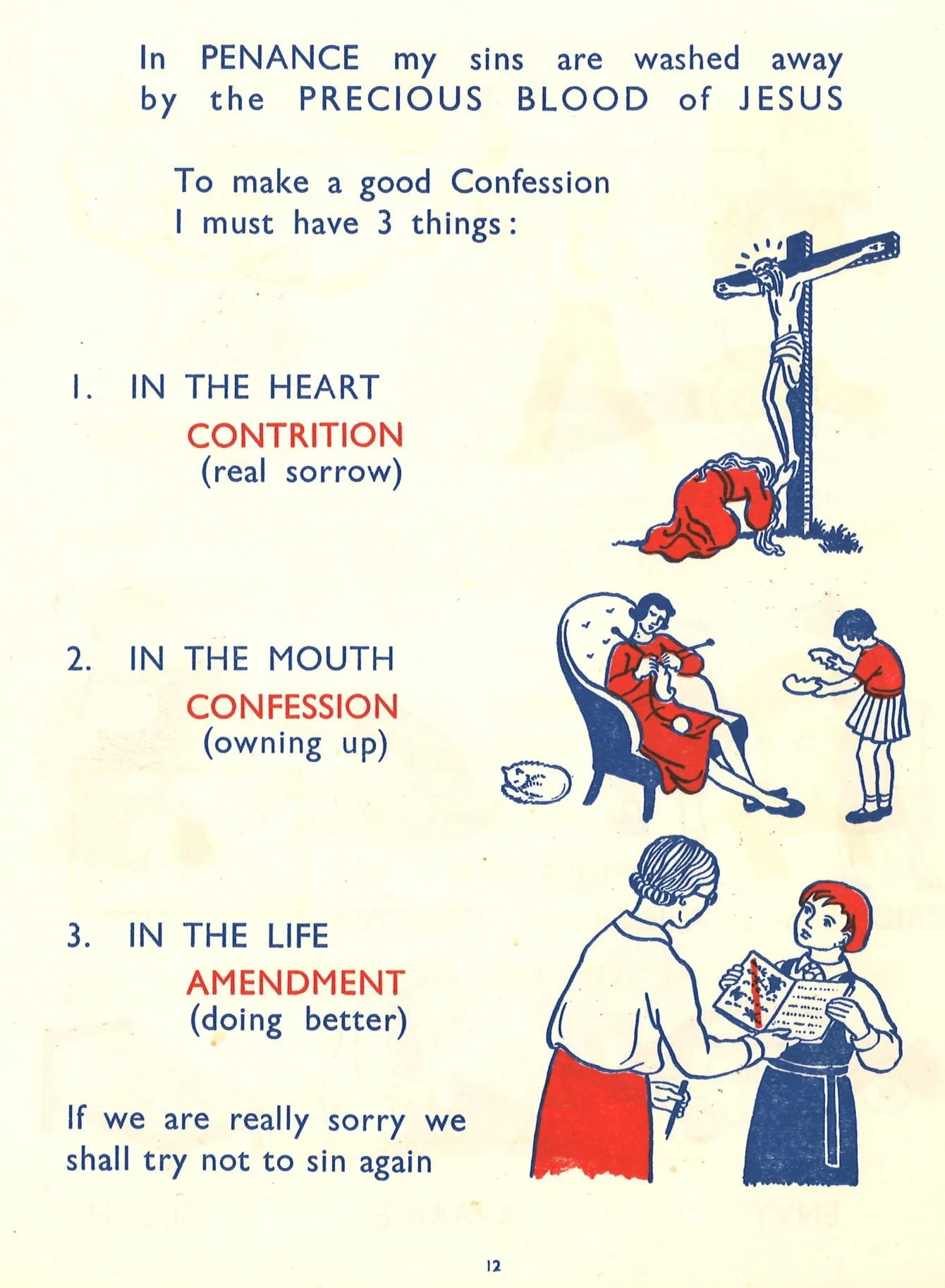

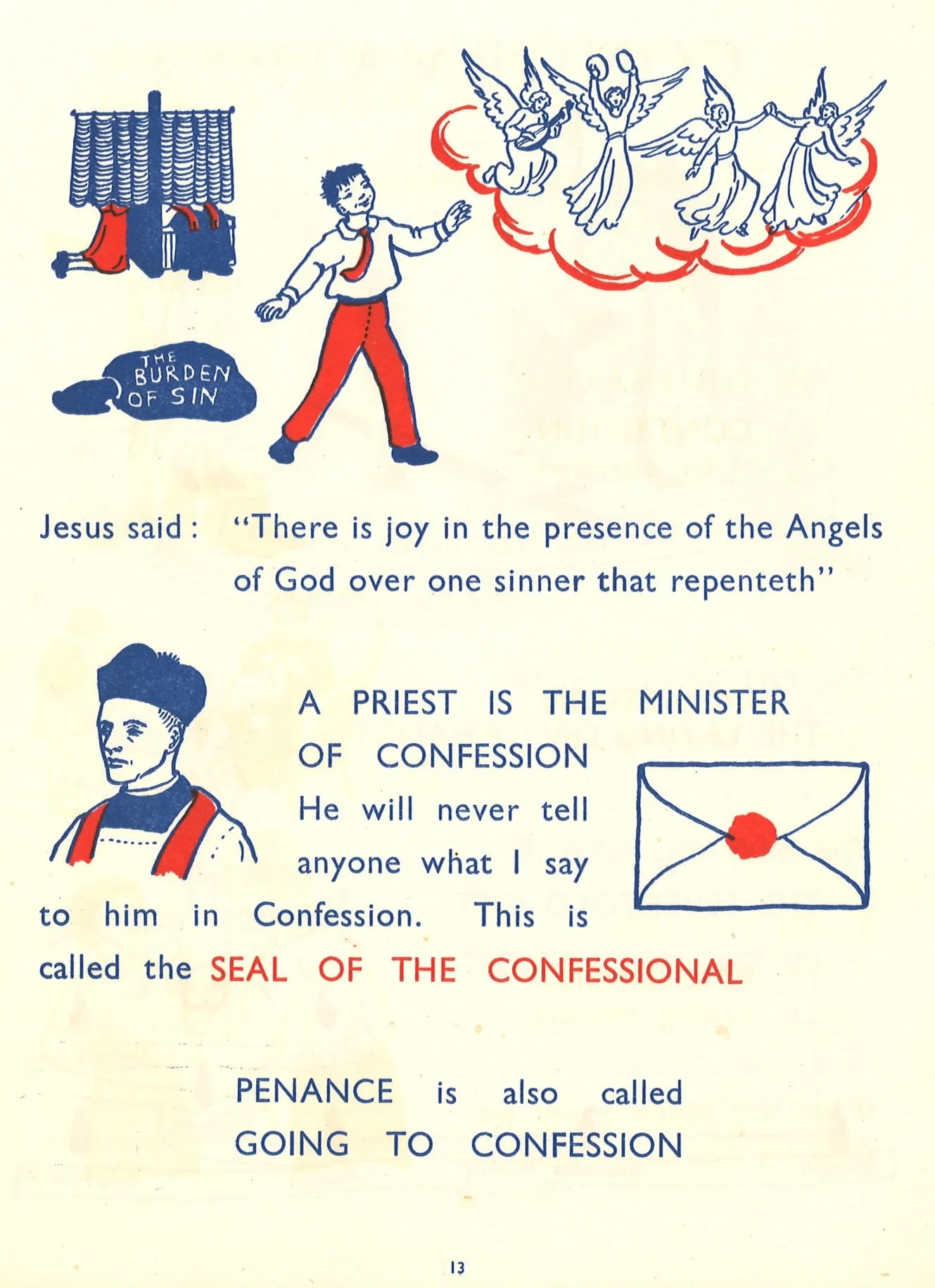

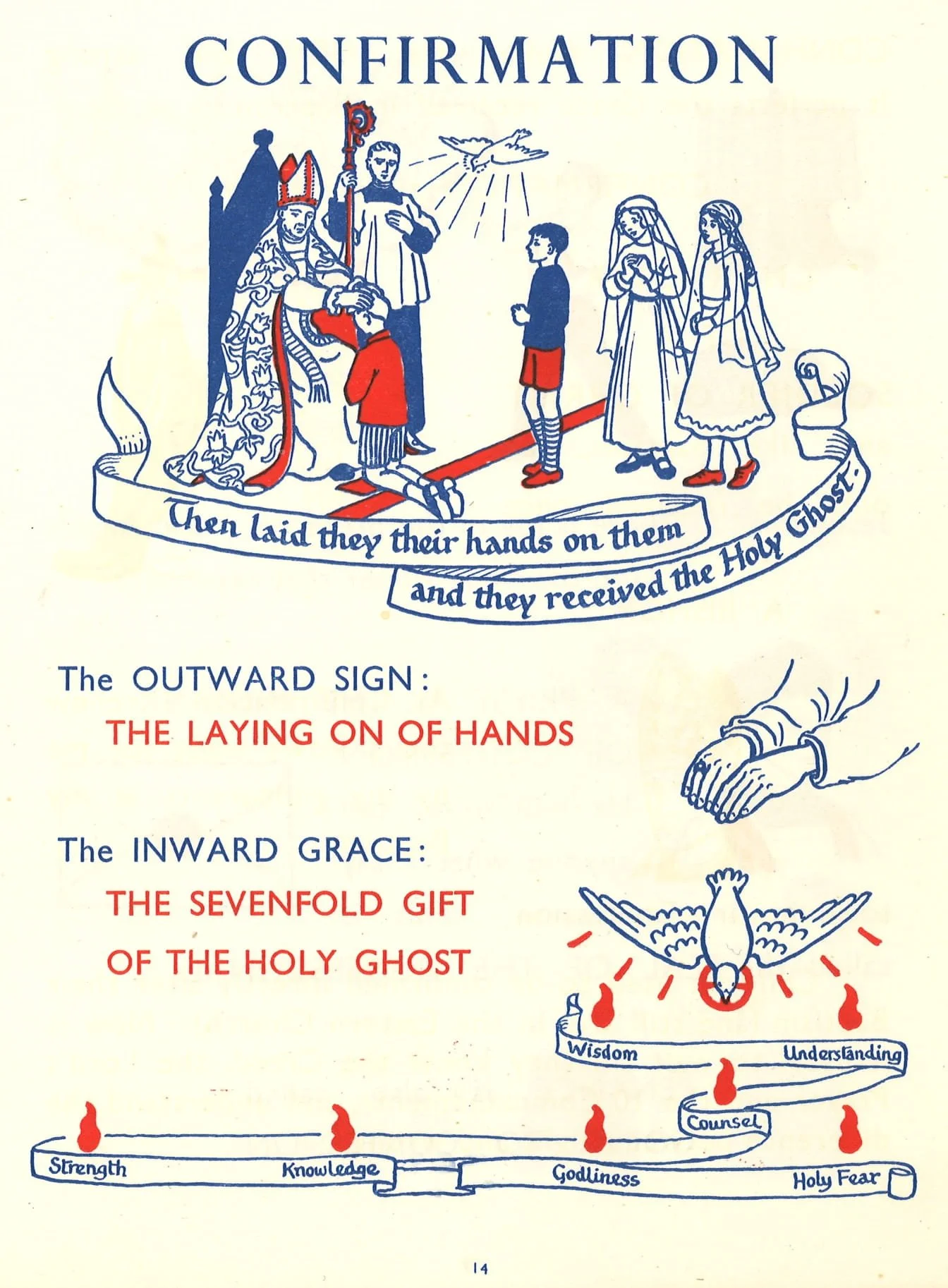

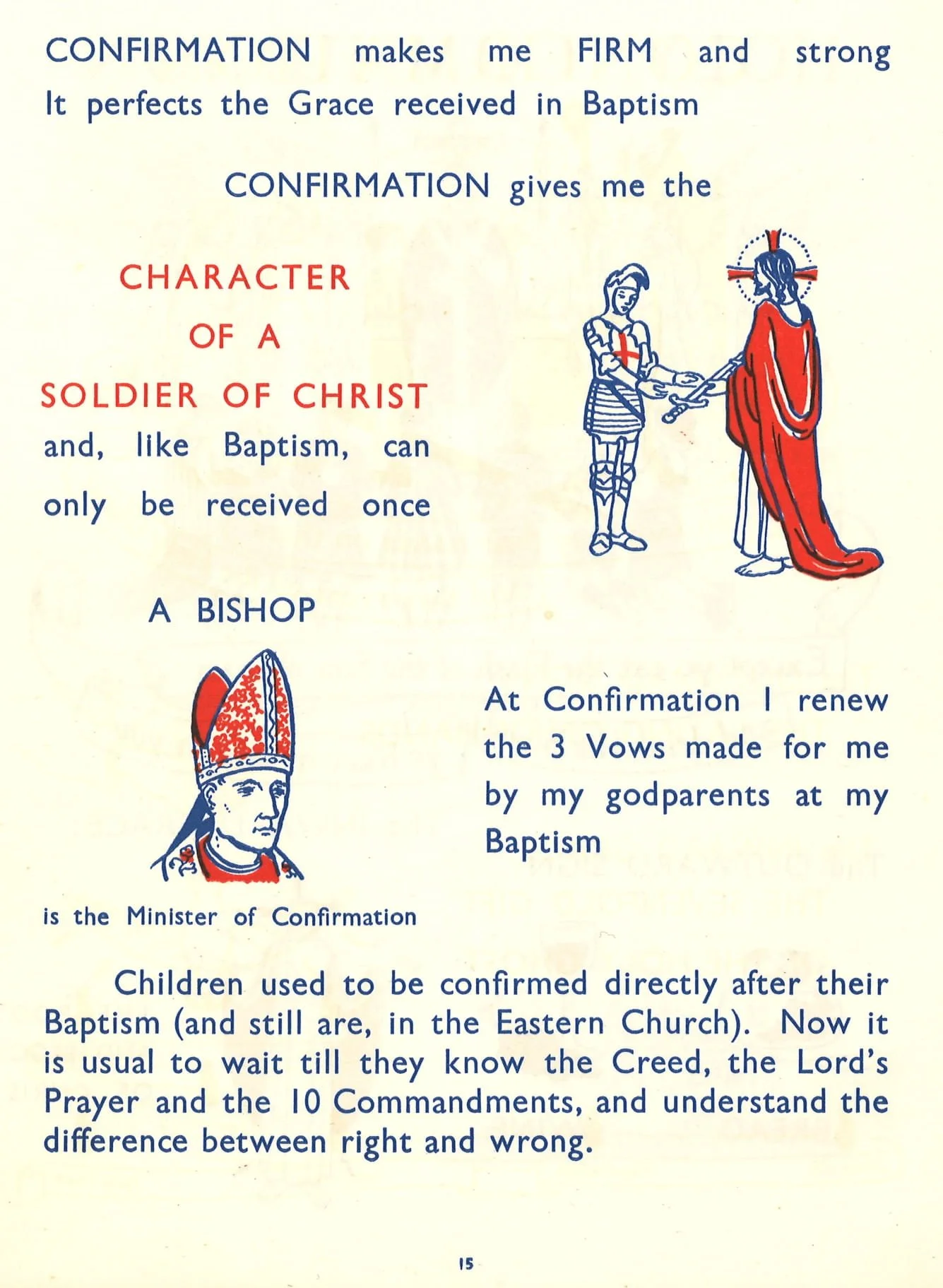

The Seven Sacraments by Enid Chadwick

Below are the pictures from the book The Seven Sacraments by Enid Chadwick. It’s a wonderful primer on how the sacraments work for adults and kids!

Announcement: Inclement Weather + Sunday Facebook Livestream + Bulletin for Sunday

O ye Winter and Summer, bless ye the Lord: * praise him, and magnify him for ever.

O ye Dews and Frosts, bless ye the Lord: * praise him, and magnify him for ever.

O ye Frost and Cold, bless ye the Lord: * praise him, and magnify him for ever.

O ye Ice and Snow, bless ye the Lord: * praise him, and magnify him for ever.

-Benedicite, omnia opera Domini (BCP 11-3)

Due to inclement weather on Sunday, January 25th, in-person services will be canceled at St. Paul’s. Because Fr. David Hodil lives across the street from the parish, he will walk over and say Holy Communion for everyone.

Since there are no in-person services, Fr. Wesley will be live-streaming Morning Prayer at 10a on the parish Facebook page.

To that end, below is a downloadable PDF of the bulletin for Sunday so that you can follow along with the service.

The Nicene Creed: “I Believe” or “We Believe”?

Note: A version of this post first appeared on Earth & Altar.

πιστεύομε είς ένα θεόν

This is the first line of the Nicene Creed in Greek. It translates to “We believe in one God.” This might seem surprising to many of the faithful who weekly profess “I believe in one God.” Why the difference?

On an historical level, we can chalk up the apparent discrepancy in the fact that, as Anglicans, we are Western Christians. When the Creed was translated from Greek into Latin, the first line read, “Credo in unum Deum,” or, “I believe in one God.” This was because the Creed was linked to the Baptismal Vows. And yet, I would argue, there’s more to it than that.

First, a brief explanation of the importance of Creeds. John Greenleaf Whittier’s poem “The Preacher” summarizes a common derogatory attitude concerning creeds: “From the death of the old the new proceeds, And the life of truth from the rot of creeds.” Many modern people assume that creeds retrain intellectual freedom and are prisons of rigid dogmatism. This lacks nuance because it fails to adequately grapple with what Creeds are. Romano Guardini offers a corrective: “He who holds to the truth holds to God.” The Creeds function as a Rule of Faith, they protect revealed facts about God who has intervened into space and time “for us and for our salvation.”

We can go further, however. A deeper understanding of the role of Creeds can be derived—surprisingly—from a work called I and Thou by Martin Buber (1878-1965), a Jewish, German mystic and philosopher. For Buber, there are two modes of relating to others: I-it and I-thou. The I-it mode of relationship consists of a subject (the “I”) acting on an object (the “it”). When a subject acts on an object, real relationship is precluded because the object’s significance is not drawn from the object itself, but from the subject’s use. While this way of relating can be helpful, like in scientific inquiry, it comes with dangers. Buber argues that I-it is inherently dehumanizing for both the I and the it. When “I” reduce another being to an object of scientific discovery, “I” am reduced to just a scientist, but “I” am so much more! We can see this play out in many ways. A biblical scholar who thinks Scripture is just another text that needs to be dissected like a biologist might dissect a frog finds themselves incapable of conversing with Scripture. We were made to relate to others as more than just things.

Buber’s alternative is the I-thou relationship. I-it approaches the other with assertions in an attempt to box the object in the “I’s” mental boxes; I-thou understands the other cannot be boxed in so easily. I-thou is a humanizing mode of relation for both parties. Buber says: “When thou is spoken, the speaker has no thing for his object. For where there is a thing there is another thing. Every It is bounded by others; It exists only through being bounded by others. But when Thou is spoken, there is no thing. Thou has no bounds. When Thou is spoken, the speaker has no thing; he has indeed nothing. But he takes his stand in relation.” In other words, I-it assumes a distance between the subject and object, but I-thou is based on an unseen yet tangible unity between parties where both constantly participate in the other. “I” am only possible because of the “you” that “I” encounter. This way of relating to others is not just humanizing for the other person, but also for the “I.” As one encounters the other, the “I” emerges. This can be confirmed by findings in modern neuroscience, particularly child development where it has been discovered that children develop into social persons based on their engagement with their parents. Self-consciousness occurs only through relationship.

While Buber’s framework is helpful, his mysticism is not rooted in orthodox Christianity and, therefore, requires some modification. For Buber, our encounters with God should be conceived as I-Thou. Buber refers to God as “the eternal Thou.” This means that faith is a meeting. His translator, Rev. Ronald Gregor Smith, remarks that for Buber, faith “is not a trust in the world of It, of creeds or other forms which are objects, and have their life in the past.” Smith would argue that according to Buber, a creed is an artifact, an inauthentic antiquarianism. This iconoclastic impulse imagines a creed as an “it” because creeds are based on propositions rather than a relationship.

Is this the right way to think about creeds? Maybe this is how the unbeliever perceives them. But where is it that we as Christians encounter the Creeds? The answer is in the praying life of the Church: we say the Apostles Creed each day at Morning and Evening Prayer and the Nicene Creed at the Mass. In that context, the Creed is more dynamic and cannot be reduced to the status of a dead artifact. The speakers should not conceive of the Creed as an “it” at all; rather, it is a dialogue occurring between the “I” and eternal “Thou.”

To better understand this way of thinking about the Creed, we have to remember the context of the Holy Communion liturgy. The Celebrant stands in persona Christi during the service. What the priest does, Christ does (and vice-versa.” The priest and Christ find themselves in the I-Thou relationship because the priest’s identity only emerges from a sustained encounter with Christ, the “High Priest” (cf. Heb 4:14-16). Anglican theologian E.L. Mascall explains, “The Bishop [the mother of the priesthood'] is not merely the organ of the earthy Church, whether of the past or of the present, but of the Church of Christ, here and beyond the grave. And the sinful man on whom priestly character is conferred in ordination receives the Holy Ghost for the office and work of a priest ‘in the Church of God’…Just as Baptism takes a man or woman up into an already existing unity, so consecration takes a man up into an already existing unity which exists within and for the sake of the former one.” The priest finds his own sacerdotal identify in the sacrifice of the Altar where his life becomes merged with the victimhood of the crucified Christ. The priestly “I” emerges in the context of the Christic “Thou.”

The liturgy is not a purely propositional reality, but a lived experience, an encounter with the Eternal Thou. The Mass is full of these encounters. The bread is not the “it” of bread nor the wine the “it” of wine; they are the “Thou” of Christ’s Body and Blood. In the Eucharistic encounter, a sacrificial pattern emerges: Christ’s sacrifice for the remission of sins and our response of self-sacrifice: “Here we offer and present unto thee, O Lord, our selves, our souls and bodies, to be a reasonable, holy, and living sacrifice unto thee.” The “I” who emerges from the encounter is cruciform by virtue of participation with Christ in his sacrifice. This is the milieu in which hate Creed is said—one in which the “I” and eternal “Thou” are in relationship.

Contrary to Smith’s assertion, the Nicene Creed is not just a set of propositions. While modern liturgies have preferred to shift to the first person plural “We believe” to highlight the fact that the Creed belongs to the Community of the Faith that is the Church, something is lost in this transition from singular to plural. Liturgically, the priest begins the Creed and invites the congregation to join him by extending and then joining his hands. But the priest stands in persona Christi; he speaks not as Fr. Wesley or Fr. David or Fr. Dennis, but Christ. The Creed speaks the Word back to the Father. To borrow from Buber, the Creed exists not as an I-it monologue of objectifying propositions but an I-thou dialogue between Christ and his Church. The Creed facilitates a relation in which the Church finds itself becoming who She is, much like the vows at a wedding bring about the bride’s self-awareness of her marital identity. The Creed invites us to see the world through the eternal Thou where our relationship with Him constitutes the bearings by which we understand everything around us. The Creed is not a list of conditions that arrogantly place God in a box; instead, it is a result of the Father and the Son’s relationship and the Church’s sustained dialogue with her Creator. There is an ecclesiological layer to this as well. The Creed unites members of the Church separated by time and space in the “I” of Christ, creating a coherent self-consciousness.

“I believe” is Christ’s declaration. In his I, we find ourselves.