The Eucharistic Fast

Have you ever heard of the Eucharistic fast? Unfortunately, in our modern world, it’s not only a discipline that has been too frequently laid aside, but forgotten entirely. According to the St. Augustine’s Prayer Book—a helpful devotional supplement to the Book of Common Prayer—the Eucharistic Fast is the abstention from food to prepare for the reception of Communion. Traditionally, this fast began Sunday at midnight and included all forms of food and water. However, this has been tweaked in modern times.

This brief post will attempt to explain the biblical and theological reasons for the Eucharistic fast, to survey he history of the practice, and to offer some modern adaptations to help us better practice the fast so that we can better prepare our bodies and souls to meet our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ in the Sacrament.

As far back as the book of Exodus, God’s people are called to self-preparation before approach God. At Mount Sinai, God through Moses gave the people of Israel a liturgy to prepare themselves:

“Go unto the people, and sanctify them to day and to morrow, and let them wash their clothes, and be ready against the third day: for the third day the Lord will come down in the sight of all the people upon mount Sinai” (Exod 19:10-11).

This careful preparation is transposed into the New Covenant around the Eucharistic meal per 1 Corinthians 11:27-29:

“Wherefore whosoever shall eat this bread, and drink this cup of the lord, unworthily, shall be guilty of the body and blood of the Lord. But let a man examine himself, and so let him eat of that bread, and drink of that cup. For he that eateth and drinketh unworthily, eateth and drinketh damnation to himself, not discerning the Lord’s body.”

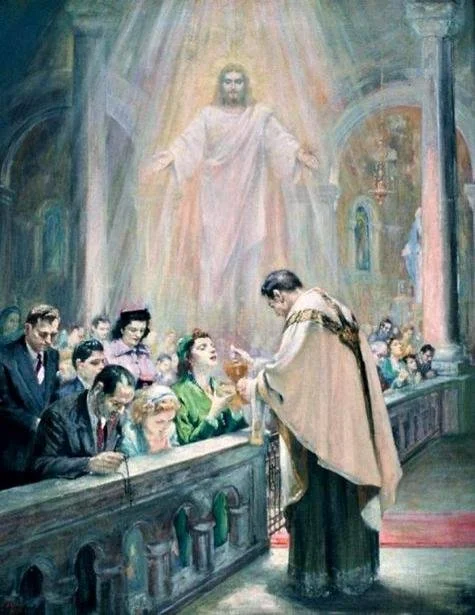

Further, both Testaments are unified in their emphasis on fasting as a way of humbling ourselves before the Lord (Joel 2:12; Matt 6:16-18). It’s important for us to remember that when we attend the Eucharist, we are attending the Wedding Supper of the Lamb (Rev 19:6-9). If one ought to carefully prepare to attend an earthly banquet, how much more should we prepare to attend a heavenly one? We can use this mode of preparation to express our reverence for the Body and Blood of Christ.

The Eucharistic fast is an ancient and venerable tradition. In its current form, the fast stretches all the way back to at least the fourth century. St. Augustine spoke of it in a letter to his friend Januarius saying:

“It has pleased the Holy Ghost that, in honor of so great a Sacrament, the Body of the Lord should enter the mouth of the Christian before any other food, for it is the custom observed throughout the world” (emphasis added).

This practice was retained in the medieval period as well. Even during and after the Reformation, many Anglicans continued to observe the Eucharistic fast. In his brilliant book The Worthy Communicant, Jeremy Taylor (1613-1667) commends the Eucharistic fast as an ancient practice, prescribing it alongside a regimen of devotional activities for each day one receives Communion. These other devotional activities include giving God thanks to receive “the sacrament of Christ himself,” making a general confession of your sins in a way that makes you keenly aware of God’s mercy, make acts of general contrition[1], worship Jesus, throw away unholy and earthly thoughts to better focus on heaven, while watching the Communion liturgy “behold with the eyes of faith and of the spirit, that thou seest Christ’s body broken upon the cross, that thou sees him bleeding for thy sins,” etc.

While the fast is commended to Anglicans, it is not required in our Canon Law or by the Book of Common Prayer. As a result, it’s helpful to look how other churches handle the Eucharistic fast. In 1953, Pope Pius XII adjusted the rules for Roman Catholics regarding the Eucharistic fast in a way that relaxed many of the rules. For example, he allowed communicants to drink water before receiving Communion. He also laxed the fasts for those who were sick, traveling, or employed as physical laborers. In 1957, he adjusted the starting time of the fast from midnight to three hours before receiving Communion. In 1983, the Roman Church adjusted the length of the fast again, requiring at least one hour of abstaining from food before reception.

One of the great things about the Anglican tradition is that it is collaborative and highly pastoral. As a result, the Eucharistic fast may not be a “one size fits all,” uniform rule. However, we would encourage that at the very least, we fast for one hour before receiving Communion. For those who are able, the traditional fast might be a richer mode of preparing to receive the Eucharist.

But it’s important that we not perform the fast just to tick off boxes; instead, we should use the fast to help us develop discipline and reference. Fasting should be a kind of physical prayer and offering to God as a way of communicating our longing for him. Fasting should help us approach the Altar with greater reverence. The physical hunger we experience during the fast should remind us to hunger for the Bread of Life.

Some practical tips for keeping the Eucharistic fast:

Don’t bite off more than you can chew (pun intended): if you are elderly, sick, or a manual laborer, please don’t try to do too much. Consider making alternative sacrifices instead of abstaining from food.

Start small: If you’re new to fasting, try starting with just an hour before Communion and adding more time as you experience success in keeping your discipline.

Coffee counts: Yes…technically coffee does count as breaking the fast. But water is okay. This is why Anglicans enjoy a hearty coffee hour after the service.

Teach children gradually: If you have children, they can begin to learn to fast in ways that are age appropriate. Older children can probably begin participating in the fast, but it might be good to teach younger children incrementally or by engaging in an alternative sacrifice.

Remember, the Eucharistic fast is not about legalism, it’s about love. When done well, the fast encourages us to come to the Altar with joyful anticipation.

“O taste and see that the Lord is good” (Ps 34:8a).

[1] The Act of Contrition according to the St. Augustine’s Prayer Book: “My God, I am very sorry that I have sinned against thee, who art so good. Forgive me, for Jesus’ sake, and I will try to sin no more” (28).